Midweek Musings...Wants and Needs

Money still doesn't grow on trees... Our mission is public education as it relates to all things forestry

Bob Zybach and I have been good friends and co-conspirators since 1993. He was up to his eyeballs in his MAIS [Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies] thesis - the day I walked into a small house he was renting in Corvallis, Oregon. The living and dining rooms were stacked so high with boxes filled with research material that it was hard to reach the kitchen.

Bob had been a successful tree planting contractor in Oregon for many years before he enrolled in the Oregon State University Department of Forest Sciences and – given work obligations – it would take him six years to complete his thesis: Using Oral Histories to Document Changing Forest Patterns in the Soap Creek Valley, Oregon 1500-1999.

He presented his thesis March 5, 1999. I had just completed a three-year tour of forests in the U.S. and Canada and was enjoying the good life on Echo Lake, just north of Bigfork, Montana. My front windows looked directly into Jewell Basin, a Mission Range beauty that overlooks the entire Flathead Valley.

By then, I had published two editions of Evergreen Magazine focusing on forestry in Indian Country, a term tribes use to describe the lands “given” to them during the dreadful reservation era that began following the Civil War. Because I am a huge fan of tribal forestry’s cultural roots I was quite taken by Bob’s MAIS though, at the time, I had no idea how important it would become as the West’s wildfire pandemic began to unfold a decade later.

Bob’s MAIS morphed into his much more ambitious PhD thesis. The Great Fires: Indian Burning and Catastrophic Forest Fire Patterns of the Oregon Coast Range 1491-1951. I finished reading it yesterday. It is a masterpiece – 451 pages of narrative, maps, charts and tables that should be required reading in every high school science/environment class in the 11 western states. Every elected official should also be required to read it. It turns most of what they think they know about western forests on its head.

More about Bob’s MAIS and PhD in a moment.

When I met Bob in Corvallis in 1993, he was putting the finishing touches on a report titled, Forest History and FEMAT Assumptions: A Critical Review of President Clinton’s 1993 Northwest Forest Plan. FEMAT – the Forest Ecosystem Management Assessment Team – made the case for listing the owl and – among other things – had insisted that there was little evidence to refute the claim that western Oregon and Washington had not been “a sea of old growth” before white settlement began in the 1840s.

Standing between waist-high rows of boxes in Bob’s house – three years after the northern spotted owl was added to the federal government’s list of threatened species – I asked a question that would become the stuff of legend.

“Bob,” I said, “where did you get all this stuff? I distinctly recall FEMAT scientists telling us this kind of information about pre-settlement forests did not exist.”

“Oh, that’s easy,” he matter-of-factly replied. “I have a library card.”

As you might imagine, his reply incensed several FEMAT scientists. In fact, two of them attempted to sabotage Bob’s PhD thesis. They failed only because two other widely respected PhD forest scientists – Robert Buckman and Ben Stout – came to Bob’s defense.

Buckman had been Director of the Pacific Northwest Forest Research Experiment Station [1971-1976], Deputy Chief of Forest Research and International Programs [1976-1986] and Vice President of the 15,000-member International Union of Forest Scientists [1986-1990].

Stout had begun his career managing Harvard’s Black Rock Forest at Petersham, Massachusetts, before moving on to Rutgers University, where he earned his PhD and taught silviculture, then the deanship at the University of Montana School of Forestry and finally the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement research facility in Corvallis.

Despite their quiet demeanors, Buckman and Stout were not to be trifled with. When I interviewed Buckman after he retired, I asked him about biological diversity in old growth forests. He looked into my eyes and said, “I will argue that there is as much or more biological diversity in a clear-cut than there is in an old growth forest.”

In retirement, Ben wrote a small book titled, The Northern Spotted Owl: An Oregon View. He artfully made the case for the fact that the owl listing decision ignored an enormous amount of research. Key data that was dismissed concerning the natural drivers that create and demolish old growth forests.

Ben thought the popularly-held notion that old growth forests could somehow be preserved for posterity was nonsense. An idea that he began to consider while under the tutelage of Hugh Miller Raup, a PhD botanist whose research led him to conclude there was no such thing as a climax forest. Basically one in which time stops and little to nothing changes for hundreds or even thousands of years.

Ben assembled an anthology of Raup’s writings titled Forests in the Here and Now. I have a copy that Ben gave me before he died in 2007. Lordy, would I have loved to interview Raup. He had no patience for group-think. His exhaustive field studies challenged the very notion that nature persists in a steady state in which equal and opposite forces balance one another. Nature and Raup existed in constant chaos.

Bob Zybach seems to thrive in the same world. No doubt to the delight of the brilliant souls of both Robert Buckman and Ben Stout. Bob is currently immersed in an effort to force Oregon State’s College of Forestry to publicly explain its eyebrow-raising proposal. A proposal that would direct the Oregon State Land Board to manage the Elliott State Forest for research purposes. A plan that would negate timber harvesting revenues constitutionally reserved for Oregon’s Common School Fund.

The story here is long and tortured, but Bob explains it in meticulous detail in Elliott Forest Boondoggle vs The Giesy Plan Alternative, in the Winter edition of the Oregon Fish & Wildlife Journal. Here. The late Wayne Giesy was one of Bob’s mentors for decades, which helps explain the photograph of Wayne and I on Page 41. He was a tireless champion of both Bob and forestry in the Douglas fir region. Bob’s essay draws heavily on both his MAIS and PhD theses.

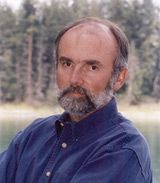

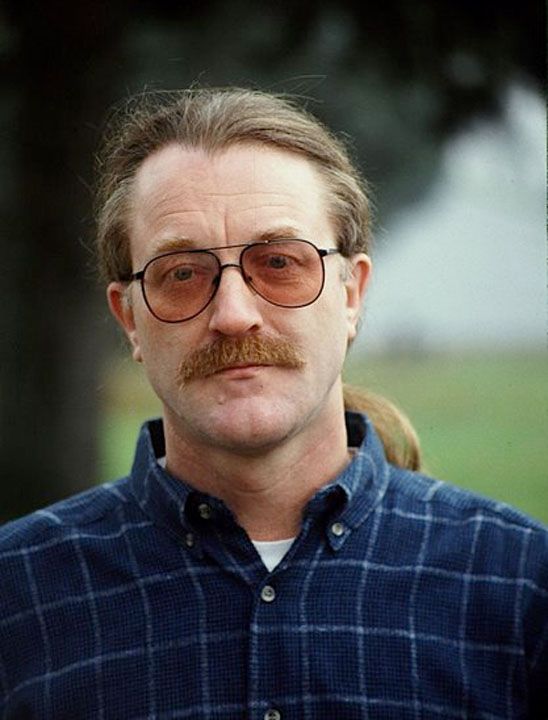

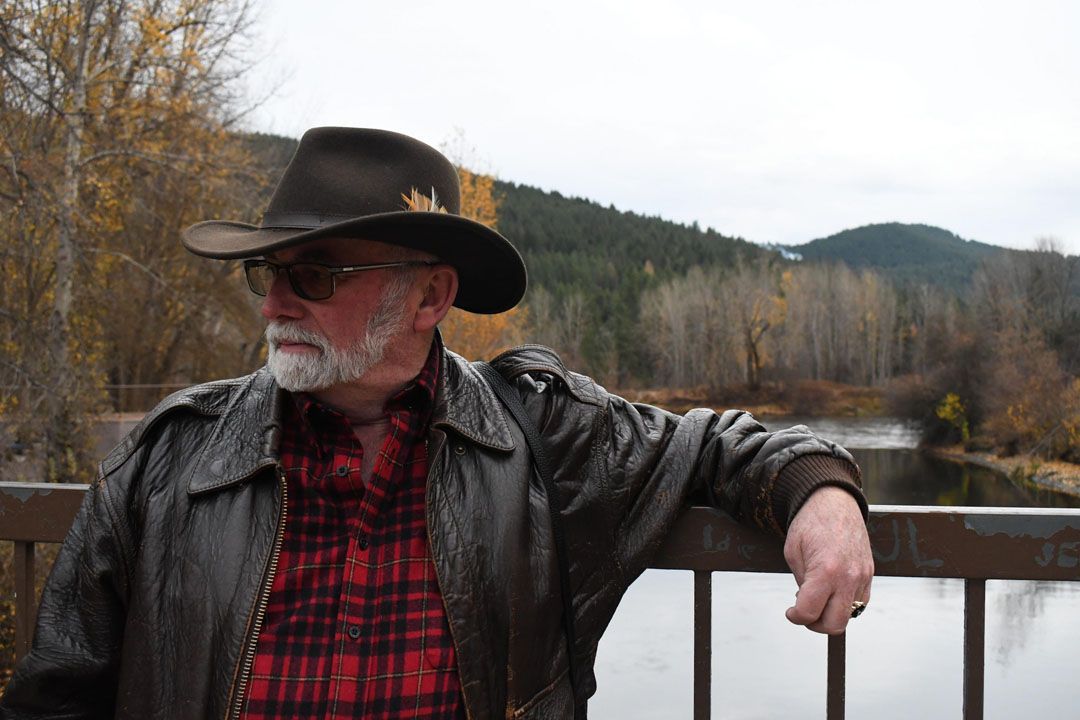

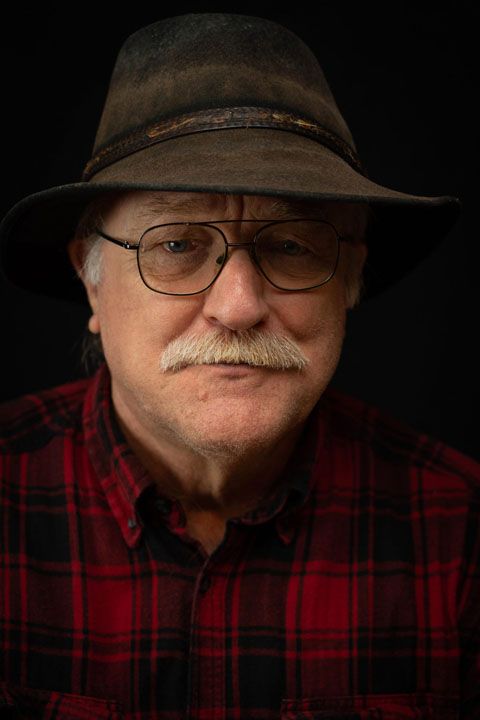

I’ll have much more to say about Bob’s MAIS and PhD research in an upcoming series of periodic essays. Suffice it to say, a lot of water has passed beneath life’s bridges since we met in 1993. To illustrate this point, I’m including photos of each of us from both eras. I am greatly amused by the fact that we are wearing almost the same damned wool shirts in our most recent photographs!

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.