“Yes, the Gap Can Be Bridged"...USFS Chief, Tom Schultz

Wildfire has become the magnet among those who share our concern for the damage stand-replacing fires have done on public

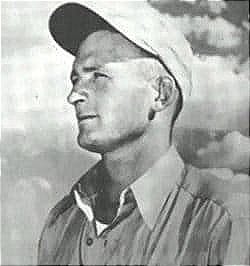

Bob Sallee, one of two Forest Service smokejumpers to survive the Mann Gulch Fire in which thirteen others perished.

What to say about the tragic deaths of thirteen smokejumpers killed by a small lightning caused forest fire that overran them after it somehow got below them in a remote gulch above the Missouri River near Craig, Montana. August 5, 1949.

In the 75 years that have come and gone since they lost their race against a mystery, the forest firefighting world has been turned upside down and inside out several times.

The mystery is how a ridgetop fire got below them in the bottom of a canyon before burning its way into tall dry grass on a steep slope. Driven by high winds, its 50-foot flames chased them up the slope at 15 feet per second.

The Mann Gulch jumpers made it about three hundred yards upslope before their crew boss, Wagner Dodge, told them to drop their tools and make a run for safety.

Then Dodge, who was thirty-three at the time, created a second mystery. He stopped in the tall grass and lit a fire that quickly assumed the shape of a dagger pointed downhill.

Most of the fire was above him toward the ridgeline, so he laid down in the dagger, but not before urging his crew to join him in the safety of burnt grass.

Terrified, they instead continued running uphill toward the cliffs. Only two made it: Bob Sallee and Walter Rumsey.

Those who perished in flames and hellish smoke:

Newton R. Thompson

David R. Navon

Eldon E. Diettert

Henry J. Thol, Jr.

James O. Harrison

Joseph B. Sylvia

Leonard L. Piper

Marvin L. Sherman

Philip R. McVey

Robert J. Bennett

Silas R. Thompson

Stanley J Reba

William J. Hellman

Of the thirteen, ten were war veterans and several were planning to major in Forestry at the University of Montana.

It was Eldon Diettert’s nineteenth birthday.

In his marvelous book, Young Men and Fire,” Norman Maclean wrote that one firefighter’s wristwatch was stopped at 5:56 p.m. This may be recorded as the time when the fire they could not outrun overran them.

And so, the second mystery: Did the escape fire that Dodge lit in hopes of saving his crew delay them for precious seconds, unintentionally contributing to their deaths?

Columnist and author John Maclean, Norman’s son, pondered these unanswerable questions during his thoughtful keynote speech at the seventy-fifth memorial on the capitol steps in Helena, Montana.

“When I talked about the mysteries with Sara Brown, program manager at the Missoula Fire Sciences Laboratory, which was founded partly as a consequence of Mann Gulch, she remarked, “They are part of the mystique that keeps us learning from the fire.”

Ms. Brown is correct. And most of what we know about the science of wildfire came because of the Missoula lab’s founding in 1960. If the lab had a spiritual founder, it would have been Harry Gisborne.

The Forest Service had named him Director of its Rocky Mountain Research Station in Missoula in 1932, ten years after he began studying the relationships between wind and fire at the Forest Service’s Priest River Experimental Forest in northern Idaho.

Gisborne is often considered the fourteenth victim of the Mann Gulch tragedy because he suffered a fatal heart attack on the trail leading from the gulch to the Missouri River on November 9, three months following the fire.

Despite a weak heart, he had insisted on walking to the site to consider a theory he had formulated about the fire’s behavior. Gisborne was accompanied by Ranger Robert Jansson, who was on the ground at Mann Gulch during the fire and the recovery operation and had participated in the decision to order jumpers. He accompanied Gisborne in hopes of finding some peace in a better understanding of what had happened that cost thirteen brave men their lives.

“Here’s a nice rock to sit on and watch the river,” the exhausted Gisborne said to Jansson on their return. “I made it good. My legs might ache a little tomorrow though.”

Those were his last words...

Norman Maclean described Gisborne’s final moments in Young Men and Fire.

“Then Jansson ran for help,” Maclean wrote. “The stars came out. Nothing moved on the game trail. The great Missouri passing below repeated the same succession of chords it probably will play for a million years to come. The only other motion was the moon floating across the lenses of Gisborne’s glasses, which at last were unobservant.”

Dick Rothermel comes as close as anyone to describing what happened on August 5 in Mann Gulch: A Race That Couldn’t be Won, a detailed assessment that he assembled 44 years later.

Rothermel’s career took him from the U.S. Air Force’s Special Weapons Aircraft Development Program to Douglas Aircraft as a designer and troubleshooter in their Armament Group and, later, General Electric’s Nuclear Propulsion Department at Idaho National Laboratory in Idaho Falls.

Rothermel joined the Forest Service’s Intermountain Fire Science Lab in Missoula, Montana in 1961 and was deeply involved in fire behavior research until his retirement in 1991.

Mann Gulch: A Race That Couldn’t Be Won “is a gripping scientific assessment of the last twenty minutes of the thirteen smokejumpers’ lives."

The high points of Rothermel’s report:

"The spot fires, which had started in heavy surface fuels, would have become intense, with flames extending into the tree crowns and climbing the tree boles."

"The tree crowns would have caught fire, and the strong gusty winds would have pushed the fire through the crowns. The crew could see a convection column of black smoke from the burning tree crowns between them and the Missouri River."

"The crew continued hurrying across the slope along an 18 percent uphill grade. The survivors reported they traveled through tall grass much of the time. Grass would have been fully cured (dried out) by August 5 at this low elevation (3,600 ft).to 20 ft. Fireline intensity would have been 2,500 to 4,000 Btu/ft·s."

"The fire would still have been burning through the crowns, but since the trees were more scattered, the surface fire was probably moving ahead of the crown fire."

"Much of what happened in the final moments probably cannot be explained simply by the fire catching up to the firefighters. Firebrands may have been falling among them, starting new fires."

"They could have continued running for some time, even after the fire caught them and was burning sporadically around them. Having said this, I still believe that Figure 2 illustrates the general course of events, even though it may not be precisely accurate."

"We see the crew increasing their pace, but the fire accelerates even faster until the lines converge—the end of a race the firefighters could not win."

On August 5th, Julia and I were among at least two hundred people who attended the 75th memorial of the Mann Gulch fire - on the front lawn of Montana's state Capitol. Attendees included state legislators, county commissioners, firefighters, news media and eighty members of the families of the thirteen - who jumped from the Johnson Flying Service C-47 - that flew them to their deaths.

Now named Miss Montana, the storied C-47 was recovered from a muddy grave at the bottom of the Monongahela River near Pittsburgh where it crashed in 1954.

“It was purchased in 2001 by the Museum of Mountain Flying in Missoula,” Maclean recalled his remarks, “where it was restored by a veritable army of volunteers and made a transatlantic flight to Europe in 2019 for the 75th anniversary of D-Day and the 70th anniversary of the Berlin Airlift.”

The beautifully painted Miss Montana made several passes over the Helena capitol before high altitude winds forced its return to Missoula, eighty-nine nautical miles southwest. I did some quick calculations and estimated that it took about an hour for the old C-47 to reach Mann Gulch from its base at Johnson Flying Service in Missoula.

When Rothermel interviewed Sallee in 1993, Sallee recalled that as the C-47 decended (picture him standing in the open door from which he and the team would momentarily jump...)

"I took a look at the fire and decided it wasn’t bad. It was burning on top of the ridge and I thought it would continue up the ridge. I thought it probably wouldn’t burn much more that night,” Sallee said, “because it was the end of the burning period (for that day) and it looked like it would have to burn down across a little saddle before it went uphill anymore.”

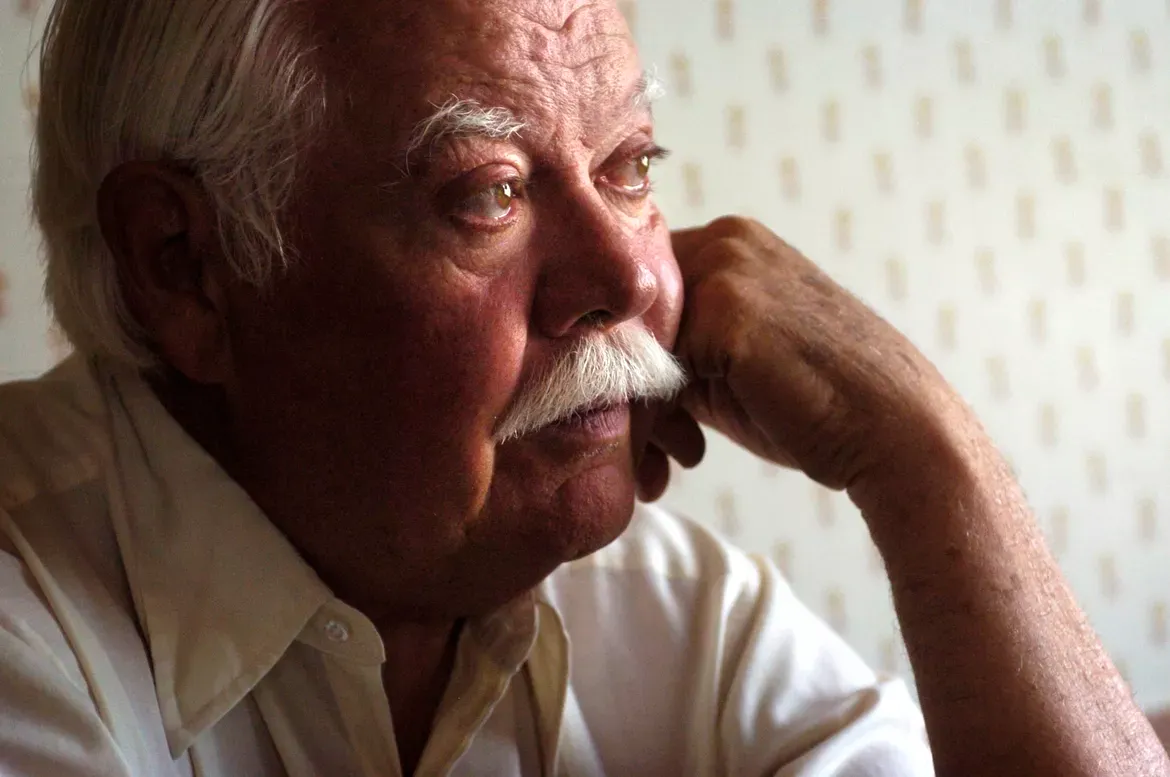

Nature had other plans that would leave indelible marks on Sallee’s life. Years later he told John Maclean the fire had left him with an emotional dead spot, an inability to feel the elations and disappointments, the highs and lows that mark the lives of others.

"Today, we would recognize this as a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder and offer ways to diminish its effects,” Maclean said, noting that Mann Gulch has not faded into obscurity as his father had suggested it might do in Young Men and Fire. Instead, it has risen from the ashes to become a cultural legacy for the wildland firefighting community, Montana, and the nation.

Although Sallee never shed his trauma, he did find a way to let go of the fire in his remarks at the fiftieth anniversary service in Helena.

"It is time to rededicate ourselves to the memory of these fine young men and the lesson they best taught us, that wildfires are, and always will be, dangerous and we must respect its potential to put a fire fighter in harm's way. Life is precious and for some very short."

Sallee enjoyed a long and successful business career. He died at 82 in 2014 and is buried in Mica Peak Cemetery near Spokane, Washington. His tombstone reads, “Robert Wayne Sallee, loving husband, father and grandfather.”

No mention of Mann Gulch. He had put it behind him.

His jump mates, Walter Rumsey and "Wag" Dodge, weren’t so lucky. Rumsey was killed in an airplane crash in Nebraska in June 1980. In a Smokejumper magazine interview, he recalled that the air was so rough that the jumpers were glad to get out of the C-47 and that the roar of the fire was so great he could only see Dodge’s lips move.

After Mann Gulch, Dodge never jumped again.

Tragically, Robert Wagner -"Wag" Dodge - died of Hodgkins Disease only 6 years later, on January 12, 1955. He was 39 years old. He requested his ashes be spread in the Idaho Powell Ranger district near some of his favorite fishing lakes.

Evergreen Director Rich Stem recalls the behind-the-scenes story of the DVD recording of “Cold Missouri Waters”.

"There was an all-Forest Supervisor/Regional Forester/Forest Service Chief meeting that took place in Nebraska approximately 18 years ago and part of the evening program was the Fiddlin Foresters performing this song.

There were very few dry eyes in the entire crowd by the time they were finished. Several Forest Supervisors came up to me and suggested that the Fiddlin Foresters should record that on a CD or DVD and use it for training of new Firefighters. An outstanding idea.

We went back and we made the decision to do just that. Dave Steinke worked with the Fiddlin Foresters and they recorded it professionally and produced a DVD. We made 500 copies and distributed them to the Washington Office with a letter explaining the utility of using this compelling song and story to impress upon new firefighters the importance of safety and the danger of firefighting. Region 2 covered the cost and we asked that they send a copy to every Ranger District and Supervisor’s office in the country. That was done.

The Fiddlin Foresters were created many years ago with the objective of education about Conservation and the Agencies mission. This recording was just one example of how they completed that in a compelling way. Our thanks should go to Dave and the Fiddlin Foresters for creating this powerful performance and for making this happen."

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.