“Yes, the Gap Can Be Bridged"...USFS Chief, Tom Schultz

Wildfire has become the magnet among those who share our concern for the damage stand-replacing fires have done on public

Money doesn't grow on trees...

Our mission is public education as it relates to all things forestry - so your contributions matter. Your support means we can continue to bring you the quality of content you have come to expect from Evergreen.

If you appreciate our work, let us know

by subscribing or donating.

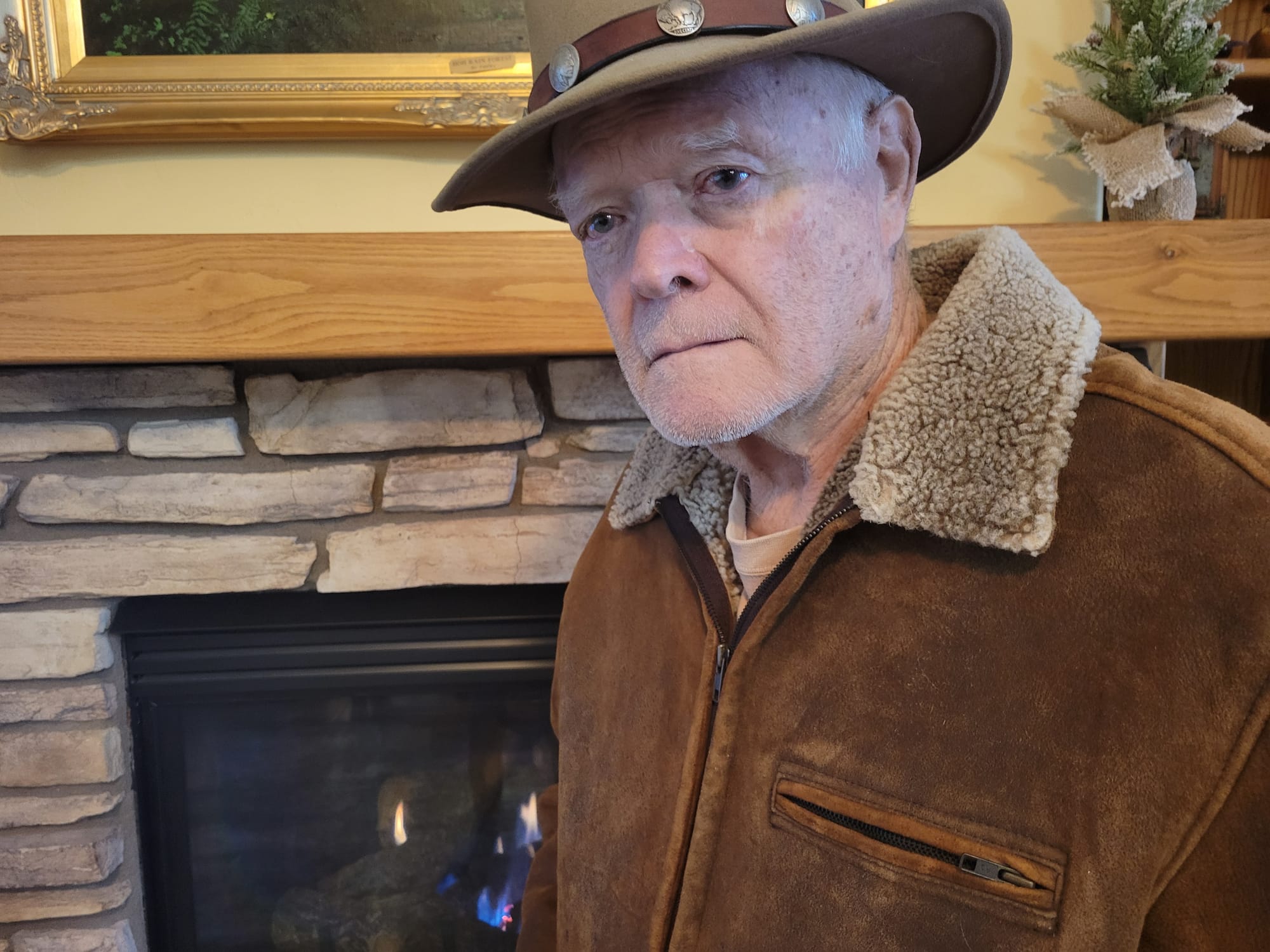

An Interview with U.S. Forest Service Retiree, Ted Stubblefield

Ted “Stub” Stubblefield is a Forest Service retiree and member of the Evergreen Foundation Board of Directors. He lives in Prescott, Arizona with his wife, Mary.

Stub grew up on a southern California avocado farm. Planting, thinning, pruning and fertilizing trees went on seven days a week. "It was hard work but choosing a forestry career just seemed like the natural thing to do,” he said of his years working in family avacado orchards.

Stub fought his first Forest Service wildfire in 1961 on a Timber Stand Improvement [TSI] crew during the summer after his freshman year at Humbolt State University in Arcata, California. He graduated in 1964 with a major in Forest Management and a minor in Wildlife Management.

TSI crews were often dispatched on wildfires at the same time as Hot Shot crews. Such was the Forest Service’s ironclad commitment to stopping fires as quickly as humanly possible. You need only look at the Sequoia National Forest’s website to see why the agency took its wildfire fighting responsibilities so seriously.

The Sequoia is graced by 38 giant sequoia groves, including 20 on the Cannell Meadows Range District where Stub worked from 1966 to 1974. https://www.fs.usda.gov/sequoia

Stub told us that he remains very proud of the single tree selection harvesting method that Sequoia forest managers were using when he arrived.

“They worked hard to reduce wildfire danger without stirring things us too much," Stub said. "You can still see the results today. Unless you know what you’re looking for there is no evidence of logging ever occurring.”

In this interview, Stub answers a series of questions that provide a jarring contrast between the Forest Service of his era and today’s Forest Service.

Evergreen: Why did you decide you wanted a Forest Service career?

Stubblefield: When I was a youngster, we camped in the Sequoia National Forest for two weeks every summer from my age four to 17. It was great fun. Then, during my college years at Humboldt State, I fought wildfires in a 24-man Timber Stand Improvement crew every summer. Having a solid retirement and health care was also a primary draw for me - even at my young age.

Evergreen: What was your first Forest Service assignment?

Stubblefield: My first temporary assignment was on the TSI crew that I mentioned. I advanced from Crewman to Crew Supervisor then Camp Supervisor for 24 men plus our cooks. We weren’t doing much timber stand improvement work. It was mostly firefighting.

My first permanent job was as a Forestry Technician, then as a GS-5 Junior Forester on the California Hot Springs Ranger District. Between 1961 and 1981, I rose from crewman to command Type 1 teams, serving as Plans Chief, Line Boss and Type II Fire Boss.

Ranking for firefighting is based totally on experience. It was unusual to advance as quickly as I did but I worked hard at it. I was a GS 11 when our crew was sent to Arizona to fight a big wildfire on the Mogollon Rim on the south side of the Grand Canyon. The Apache National Forest District Ranger outranked me but the fire was mine to fight. He wanted nothing to do with it after I explained how we were going to put it out. And we did.

Evergreen: What was the Forest Service’s mission statement in this era?

Stubblefield: In my early years, I don’t think we had one, but my focus and my main mission was to plant trees. I also surveyed special use property boundaries and laid out small timber sales. Later, the Sequoia sent me to the Cennell Meadow Ranger District. I had to contend with the Kern Plateau because I was the Timber Sale Administrator on the biggest logging operation in southern California. Forty log trucks per day – a combination of ponderosa, sugar pine, red fir and white fir that had a lot of rot in it.

There are no sequoia trees on the Plateau but it’s a 950 square mile high elevation summer retreat for people who want to escape the heat in the valleys. Congress had been discussing management options for years – including a no harvest Reserve for the Plateau - so we were very careful about what we did and how we did it. I memorized our timber sale contracts and read a 60-inch tall stack of congressional paperwork that helped me understand what was necessary.

Evergreen: My goodness, did you enter a training program or have mentors to help you figure out what you could and could not do?

Stubblefield: A GS-7 Forester was my immediate mentor. The Forest Timber Management Officer required every Forester and Forest Technician to pass a 2-week training program in scaling and timber cruising every year on the Sequoia National Forest. Later, Sale Administration was added to the training program. The classes were tough.

Evergreen: Were you encouraged to get involved in local civic groups?

Stubblefield: Not until I was living in larger communities and I had advanced to GS-9 status. Then it was everything from Rotary Club meetings to auctions, art shows and some cattlemen’s groups. I really enjoyed getting to know people in those communities.

Evergreen: How were promotions earned?

Stubblefield: The Forest Service used a merit rating system unless your position had been upgraded in which case you were promoted in place if they chose to retain you.

Evergreen: Did you expect to be transferred frequently or infrequently?

Stubblefield: We expected to be transferred every three or four years but I was promoted three times over eight years and three jobs without changing my permanent location.

Evergreen: What was Job One - your highest priority?

Stubblefield: Job Number One was to reach your assigned annual timber target. With our top notch crew, we developed the only 10-year sales program in Region 5. We worked out tails off. Phil Aune, who is also on your Evergreen Board, was our sale preparation guy. We could all do all the jobs. Hard work made us strong. We loved it. No one complained.

I was never an armchair guy because I preferred being in the brush where things that were my responsibility were happening. Being stuck in an office drove me nuts.

Evergreen: You career began in the era before the Decadal Forest Plans came along in the mid-1980s. What sort of planning did you do before 10-year-plans were set in motion by Congress?

Stubblefield: We did Timber Plans in the early 1960s. Then broader-based Multiple Use plans came along. Then we did what were called Unit Plans. All of this occurred before computers and Decadal Forest Plans came along.

Evergreen: On Montana's Kootenai National Forest they used large sheets of opaque tissue paper and colored pencils to draw in all of the natural resources they were responsible managing. To get the same layering effect computers offer today, they laid the tissues on top of one another.

Stubblefield: No, we used what the Forest Service called “Idea Books.” They were three-by-five inches, so you could stuff them in shirt or jacket pocket. I had dozens of them. Each book described a different timber sale in great detail.

I kept notes on everything we were doing or were planning to do on a timber sale, including Position Statements. We needed to be able to explain why we were going to do what we were planning to do. Then came the Timber Sale Plan, the Timber Sale Contract and, finally, the Oral Auction where timber was sold to mills that manufacturer lumber or plywood.

Evergreen: How did the Forest Service command to “get out the cut” fit into your planning process?

Stubblefield: Contrary to what some people believe, we were never out cutting trees wherever we wanted just for the joy of it. As late as the 1970s, timber sales were hard targets associated with our detailed Forest Management Plans, Timber Sale Purchase Agreements and associated timber sale monitoring.

These targets became impossible to meet during the 1980s spotted owl wars because of timber sale appeals and litigation. It was a very frustrating time for those of us who believed that the only way to grow forests and protect them from insects, diseases and wildfires was to manage them properly and to replant as quickly as possible after logging or wildfire.

Evergreen: Was this hard targeting process the same in every western National Forest Region?

Stubblefield: No. We were more multiple-use oriented in Region 5. In Region 6 you were well advised to make your annual cut or explain that you were being sued. Region 6 was the Douglas-fir region and it included the best timber growing lands in the West.

The post-World War II housing boom in western states was powered by Douglas-fir timber clearcut from federally-owned forests using increasingly sophisticated and expensive logging systems capable of reaching trees more than one mile away from where they were felled.

Most of the timber felled in support of the war effort came from private lands in the Pacific Northwest. Federal forests became the major domestic timber supplier during the Truman Administration years following the war.

Evergreen: I know the transition began with a lot of roadbuilding in National Forests. They were largely inaccessible before that.

Stubblefield: There were a few roads - most built by miners - but not many and certainly not enough to support the major forest management program that was developed following World War II.

Evergreen: Did the Forest Service employ “ologists” in your era?

Stubblefield: We had hydrologists and soil scientists in the Region 5 regional office and on the Sequoia National Forest in the late 1960s and early 1970s and at all levels after Congress approved the National Forest Management Act [NFMA] in 1976. It mandated forest plans that balanced timber harvesting against all other forest resources including soil, water and fish and wildlife habitat. NFMA was the precursor to Decadal Forest Plans.

Evergreen: Were there internal conflicts over the Forest Flans you were developing?

Stubblefield: Not in Region 5, but in Region 6 there were absolute refusals to change and District Rangers and Regional Foresters who went along with not following the 1976 revisions in the National Environmental Policy Act [NEPA] if following the revisions meant annual harvest targets could not be met.

NEPA requires all federal agencies to measure the environmental impacts of their proposed actions before they proceed. It is the genesis of mandated Environmental Impact Statements [EIS] and Environmental Assessments [EA].

Evergreen: It was a challenging era for old school foresters, wasn’t it.

Stubblefield: For some, yes, and for others less so. It depended on the Region you were in and who you answered to. Some people in leadership positions were old school hardliners. Others adapted more easily to changing political times and increasing regulation.

Even in retirement, my main concerns are still focused on regulations and policies that have led to the loss of millions of acres of beautiful old growth and second and third growth planted by crews in my era. I don’t think most people understand what’s being lost or the hundreds of years it will take to get it back.

Evergreen: I agree but that's a story for another time. What career track did you follow in the years leading to your retirement?

Stubblefield: I was the District Ranger on the Ukonom District of the Klamath National Forest from 1974 to 1977. District lands were checkerboarded with the Karuk Tribe's Ancestral Lands so, while I was there, I got involved in Karuk Tribe ceremonial dances and established a successful working relationship with the tribe's Chief.

Then, from 1977 to 1979, I developed and led a cadre of experts teaching NFMA rules and regulations to more than 6,000 federal employees in multiple regions and the Washington, D.C. office.

Evergreen: How did you enjoy working with northern California’s Karuk Tribe?

Stubblefield: Very much, but it was really tense when I arrived in Somes Bar. The Ukomon District Ranger was so afraid of the tribe that he had ordered the installation of concertina wire around part of the Forest Service compound.

I had it removed, but the first time I went to a meeting with the Tribe I was spit on several times before I reached the front of the room where the Chief was sitting. I kept walking and didn't react. They were angry at the previous District leadership because it wanted the Tribe to pay for access to one of their ancestral religious sites. I thought it was nonsense. The Chief and I eventually developed a respectful relationship, so I started attending tribal ceremonial dances. We became good friends. It was a satisfying experience.

Evergreen: We’ve been working with the Intertribal Timber Council for 40 years. The learning curve was steep and challenging but we’ve learned a great deal about tribal forestry - which we support - and we just renewed our ITC memberships.

Stubblefield: Several tribes in the West do an excellent job of managing their forest and rangelands.

Evergreen: We agree. What came next on your career track?

Stubblefield: Reluctantly, I went to the Region 5 office in San Franscisco for two years to handle training on National Forest Management Act regulations. I worked with line officers – Forest Supervisors and District Rangers – on every National Forest in the Region.

Evergreen: Why were you reluctant?

Stubblefield: San Francisco is a big city. The transition is difficult for a country boy, but I made the best of it.

Evergreen: Then what?

Stubblefield: I was Timber Staff Officer on the Siskiyou National Forest based in Grants Pass, Oregon from 1979 to 1985. Bill Ronayne had retired and Bill Covey was the Forest Supervisor. I believe you started Evergreen in 1985. Am I correct?

Evergreen: You are correct. I got to know Bill Ronayne during the big clearcutting dustup that developed in the Douglas-fir region in 1971. I was then a reporter with the Grants Pass Daily Courier. He provided a great interview for a series of articles that the late Oregon Congressman, John Dellenback, later placed in the Congressional Record.

Stubblefield: It was a wild and woolly era. The Forest Service was 10 years into the 1969 National Environmental Policy Act – which required 100-foot buffers on both sides of live streams - and Region 6 leadership in Portland was still turning a blind eye to big clearcuts and high lead logging cables dragging big logs through spawning streams. We stopped all of that with contract changes.

Evergreen: I encountered lots of discontent in southern Oregon when I was researching the clearcutting series I wrote. Even people who wanted to defend clearcutting thought there was too much of it going on. Where did you go when you left Grants Pass?

Stubblefield: I was Forest Supervisor on the Olympic National Forest from 1985 t0 1991. We were based in Olympia, Washington and I had 250 people on my staff. When I arrived, I found the same riparian zone mess I found on the Siskiyou and we fixed it again.

Evergreen: Was the Olympic your last assignment?

Stubblefield: No. I was named Forest Supervisor on the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, based in Vancouver, Washington. I had a $55 million annual budget and supervised a staff of 650 permanent employees and 1,500 temporaries. I was very fortunate to have Rich Stem – another Evergreen board member – as my Timber Staff Officer. I knew what kind of a guy he was. I could hand him the toughest jobs and get out of his way and he could usually fix the problem.

Evergreen: Lots of spotted owl litigation. A tough act to follow.

Stubblefield. It was – so I retired after 38 mostly very rewarding years.

Evergreen: Got time for a few more questions?

Stubblefield: I have nothing but time. Fire away.

Evergreen: When you were a Timber Management Assistant, what were your days like?

Stubblefield: It varied. I did a month long detail in the Region 5 Regional Office working with George Leonard, who went on to become Forest Service Associate Chief. My task was to do Operator Cost Analysis, basically logging and wood processing operator costs analysis. It was a great learning experience.

I also did several Details in the Washington Office, writing regulations, reviewing Regional Timber Programs and hosting an NFMA training session. I soon learned is that the words “shall,” “should” and “may" have powerful meanings. Congressional intent can get lost between ratifying the law and actual implementation in the field. If the word "shall" appeared in a regulation, you damn well better do it.

Evergreen: Those were busy years for you!

Stubblefield: They were. I was also part of the largest contingent of U.S. foresters to review timber operations in Finland, Sweden and Norway and to compare their export programs to the U.S. export program. We also got to observe and compare their logging equipment with what our loggers were using. The Scandanavians were far ahead in terms of light impact, light-on-the-land logging systems.

I also taught classes on our National Timber Sale Planning Process at Clemson University, Oregon State University and a few Regions, including Region 5. The late Regional Forester, Doug Leisz, required a one-day session for every forest Supervisor and District Ranger. We had 6,000 people in Region 5 who were variously involved in preparing sales.

Evergreen: Today, there seems to be lots of planning for its own sake – analysis paralysis some say - and not much on-the-ground execution. True?

Stubblefield: Planning and appeals or lawsuits consume the majority of time for too many people. Forests that face constant appeals have established Teams that work on appeals and lawsuits.

By contrast, in the 1980s, our workforces hit the deck running to meet their hard targets. But by the time the owl wars ended harvest levels in Region 6 had fallen by 85 to 88 percent and harvest levels on the remaining 10-12 percent were not met. Worse, there was little to no accountability or standards for measuring job performance.

Evergreen: Our sense is that the concept of execution is not well understood in the present-day Forest Service. Do you agree?

Stubblefield: Execution is very spotty because few are held accountable for what they got done and didn't get done. In my later years, those of us who did achieve were often unable to meet our targets because of timber sale appeals. Today, there are too many Line Officers with little to no fire experience or qualifications, and too few that know how to meet expectations and hold people accountable. In my era, we were guided by knowledgeable leaders with decades of field experience.

Evergreen: Many refer to today’s Forest Service as “the Fire Service.” Is this a fair assessment?

Stubblefield: The agency’s budget numbers speak for themselves. There was a time when the timber portion of the budget was about 70 percent of the total budget. Today, some 60 percent of the Fire Budget goes toward Fire Management. The agency is not addressing the underlying causes of these increasingly frequent and destructive wildfires. Today, only fire personnel work fires. In my era, everyone knew they might be called to help fight fires.

Evergreen: “Managed fire for resource benefit” is today’s mantra. The Forest Service seems to have given up on actual thinning and prescribed burning to reduce wildfire risk because it fears litigation. Do you agree?

Stubblefield: About 10 years ago, two scientists and the Director of the Station, developed the notion of “managing WILDfire for long term ecosystem benefits.” Then, the Deputy Chief for Fire and Aviation, promoted the concept to the Chief, who accepted it and “put it in his tool box,” according to the quote from the Director of Fire and Aviation at the time. It’s still there.

This Chief’s policy went down the line to all Regional Foresters, and subsequently to each Forest Supervisor and Type I Incident Commander and Management Team. Since then, about five percent of these fires have been monitored for 6-10 days before a decision is made to suppress or not suppress the fire. In the interim, these fires sometimes grow to thousands of acres and are totally out of control.

The news media had a field day reporting on the 2022 Calf Canyon-Hermits Creek Fire in New Mexico. About 341,000 acres were lost and more than 900 homes were destroyed. This was a prescribed burn that was set by an inexperienced crew on a day when it was too windy. Repairing the damage has cost taxpayers about $5 billion. Yet the Forest Service continues to partially count acres lost in big wildfires as "acres restored for ecosystem benefit."

In my era, logging was the primary forest management tool because it produced so many benefits: Logs, jobs, money for county schools, roads and recreation projects and dollars for wildlife, fisheries and fuels reduction projects. There was strong public support for what we were doing.

Evergreen: There doesn’t seem to be much “resource benefit” in allowing Threatened and Endangered Species habitat to be purposefully burnt to a crisp. Likewise, old growth and “future old growth.” Or any of the other aesthetic values the public treasures. What am I missing here?

Stubblefield: Nothing. In my era, our timber budget included money for pre-commercial and commercial thinning because the practices were seen as good tools for stimulating growth in residual trees. They also kept the fire danger low and generated additional funding for more projects. Little of that occurs today.

Worse, salvaging dying and dead timber rarely occurs because the Forest Service fears it will be sued. Salvage is a red flag for those who believe nature knows best. Even when the agency wins in court, the value of the wood is lost before salvage work can begin.

You have an Director on your Evergreen Board who has shown several National Forest staffs how to overcome this problem by preparing Environmental Impact Statements and Environmental Assessments that Federal Courts approve.

Evergreen: We do have the Director you reference on our Evergreen Board and he is on my interview list. Thanks for your time today Stub. You’ve done a great job of contrasting the Forest Service of your era with the agency of today.

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.