Bill Hagenstein's Prediction

Bill Hagenstein and I were friends for 43 years. He inspired my early interest in forestry. I first interviewed him

Wesley Rickard, my late father-in-law, was a forestry legend. He was the old Weyerhaeuser Timber Company’s first forest economist, and is widely credited with having “invented” high yield forestry in the late 1960s.

It all started when George Weyerhaeuser Jr. presented Wes with a hypothesis. “Pretend we are doing everything wrong - forget everything we think we know - and tell us how to do it.”

Back then, Weyerhaeuser was all about growing and harvesting timber to feed its sawmills and plywood plants. Its board of directors was proud of the fact that they were growing enough timber to sustainably supply their wood processing network forever.

At GW's request, Wes assembled a team of like-minded stargazers and went to work. Their starting point was a large collection of western Washington soil samples collected by the late George Staebler, who was then overseeing the company’s trendsetting research lab at Chehalis, Washington.

Wes’ quiet modesty prevented him from ever accepting credit for what he’d done. However, we have dozens of boxes of his research and there isn’t much doubt about the fact that Wes is the one who built the framework for what he called “target forestry.”

Wes disliked the “high yield” moniker devised by the whiz kids at Cole and Weber advertising in Seattle.

“It doesn’t tell me anything, and it is misleading,“ he explained when I asked him why he objected to the "high yield forestry" brand.

"Target Forestry told you what you had to do to meet your objective. Weyerhaeuser Jr. hoped we could figure out how to grow trees faster, but we could have just as easily asked the computer model we built how to grow a particular type of habitat, or a mix of tree species.”

Wes and his colleagues spent nearly three years writing code and stuffing IBM punch cards into a mainframe computer. Eventually, they found the answer they sought.

Wes started his own consulting firm in 1967 – Wesley Rickard Inc., Forest management, policy, and economics. He worked for 50 years consulting and as an expert witness in all things forestry related.

Wes died in 2016. Amongst his life work, we found boxes of these cards – numbered and bundled. They were part of the evidence used in many litigations. The proof of land misuse and valuation of damages as calculated by the expert witness, Wesley Rickard. We brought home a box of those old cards - to remember how far developing formulas and writing code has come. I haven’t a clue what they say but they changed the forestry world forever.

“What do you want from your forest?” This was Wes' focus when working with clients. It was the first question he always asked when posed with a forestry question.

If you could describe what you wanted: younger trees, older trees, habitat for specific species, a better watershed, a different mix of tree species, sacred ground, overall forest-to-community health...Wes could tell you what was needed to do to meet your objective.

Forest Service Chief, Jack Ward Thomas quit in disgust in 1996. Afterwards, I asked him what he thought the agency’s management objective had been during his three years at the helm. After a long pause, he said, “I think it was to conserve late succession species.”

“Did you do it?” I asked.

“Hell, no,” he replied.

To his great credit, Jack tried to convince the agency’s congressional handlers that leaving the nation’s 190 million-acre federal forest estate in nature’s hands was not a good strategy. Few listened and many were openly hostile to the idea that active forest management was key to conserving late succession species – old forests and all the creatures that live in them.

The wildfire pandemic we are witnessing today is a direct result of congressional refusal to consider risk management. Time-tested watershed-scale strategies for unwinding the risk of catastrophic wildfire in forests the public loves. Forests that provide millions of habitat niches for birds, mammals, fish, amphibians and a vast array of plants and subterranean life forms.

Private landowners, states and Native American tribes that own timberland have been managing risk – and conserving habitat in their forests for decades.

Meanwhile, Congress continues to genuflect before powerful anti-forestry groups. People who see nothing wrong with half-million-acre, stand-replacing, wildfires. These same individuals want you to believe thinning the same half-million acres so as to reduce the risk of wildfire - is an “environmental disaster.”

Our forests, our public lands belong to all 331 million of us – not the high-minded few who are driving narratives and making decisions about places where they’ve never been. I’m sick of their elitist attitudes and their breathtaking arrogance.

These people are morally bankrupt.

If anyone could claim ethical authority in the quest to rescue our national forests from wildfire, it is those who proactively work to maintain forest-to-community-health. It’s the forest collaboratives - volunteer groups who work tirelessly to help the Forest Service develop projects designed to restore natural resiliency in dying forests.

Smokejumpers and the wildland firefighters, the dirt foresters and hard working loggers. Those on the ground that have local knowledge - and the capacity for good judgement. These are our stewards. The people who are capable of rescuing our forests. Not the serial litigators or the gumshoe lobbyists whoring in House and Senate office buildings.

Maybe if House and Senate members were forced to breathe wildfire smoke for two or three months every summer, walk the millions of acres of incinerated forests, watch a mega-fire melt soil, boil water and suffocate wildlife, or spend time with families who have lost everything - including loves ones. Maybe then they’d understand why so many are so fed up with their willful ignorance.

Sunday, June 30, marked the seventh anniversary of the Yarnell Fire near Prescott, Arizona. A fire that resulted in the loss of 19 members of the Granite Mountain Hotshot Crew.

In June of 2013, the Weaver Mountains surrounding Yarnell were suffering an extreme drought. The area had not experienced a wildfire in 47 years. The chaparral had grown as tall as 10 feet. Wind, heat, drought, failed radio transmissions, equipment failure, and no air support - all contributed to the tragedy that unfolded. It is a grim reminder that wildland firefighting can be a tough and deadly business.

The moral authority here rests with those who continue to argue the case for stewardship. Doing the thinning and stand tending work necessary. The work that reduces the risks wildland firefighters face every time the alarm sounds.

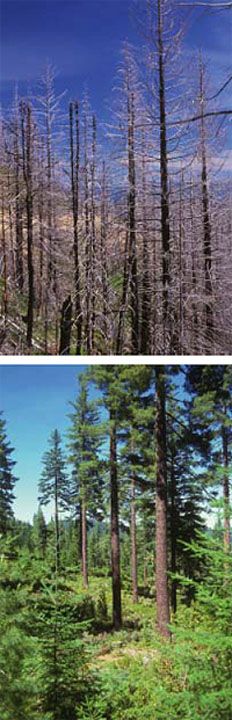

Here are two photographs. One is a thinned forest, and the other is the same forest after it was torched by wildfire.

Which forest do you prefer? I like the green one.

I want wildfires to be immediately contained (Rapid Initial Attack) and forests that aren’t death traps for those who risk their lives on fire lines. Our forests should not be hazards to adjacent communities. I want our forests to provide clean air, clean water, abundant fish and wildlife habitat and a wealth of year-round outdoor recreation opportunity.

In the words of Wes Rickard...

What do you want from your forest?

Consider purchasing a copy of our book "First put out the FIRE!" Learn more about how we can keep our forests resilient and foster forest-to-community health.

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.