“Yes, the Gap Can Be Bridged"...USFS Chief, Tom Schultz

Wildfire has become the magnet among those who share our concern for the damage stand-replacing fires have done on public

“The first obligation resting upon the management of national forest timber is to supply legitimate demands. The requirements of communities and industries in the localities adjoining the forests represent such a demand…

The second responsibility is to secure sufficient revenue as soon as practicable to pay for their upkeep and compensate western states for withholding of property from taxation. These are public burdens which cannot be ignored…

A final test of good management of the national forests will be to prevent loss of timber through waste or deterioration as far as practicable and to improve their commercial value and productivity through the application of forestry.”

William B. Greeley, Assistant Forester, U.S. Forest Service, Some Public and Economic Aspects of the Lumber Industry, U.S. Department of Agriculture Report No. 114, March 1917

I can’t help but wonder what Bill Greeley would think on learning that about half of our National Forests – nearly 100 million acres - are dying, already dead or burnt to a crisp.

Greeley, the third Chief of the U.S. Forest Service – and arguably its greatest – would be horrified. What he called his “terrible New England conscience – had no room for such waste.

He even disapproved of the Indian use of what he called “Piute fire, prescribed burning tribes used to maintain the character of northern California’s savannahs. From the 40 years we worked with Indian Forest Management Assessment teams we know Greeley was wrong.

The same horror that would have befalled Greeley would have also gripped his boss, Gifford Pinchot, the Forest Service’s first Chief. He was trained at the French National School of Forestry and was the the second professionally trained forester in the United States, the first being Bernard Fernow.

Likewise, Henry Graves, the agency’s second Chief and the former Dean of the Yale University School of Forestry Graves and Pinchot were charter members of the Society of American Forests together five other charter members. Among them, E.T. Allen, a brilliant young man who, in 1909, became the Western Forestry and Conservation Association’s first forester.

Greeley finished at the top of Yale University’s first forestry graduating class in 1904 and was handpicked by Pinchot to be the first Region 1 Forester. Then known as District 1, the remote region spanned 41 million acres – all of Montana, northern Idaho and the northeast corner of Washington. The eastern two-thirds of Montana was mostly grassland but western Montana, northern Idaho and northeast Washington were heavily timbered.

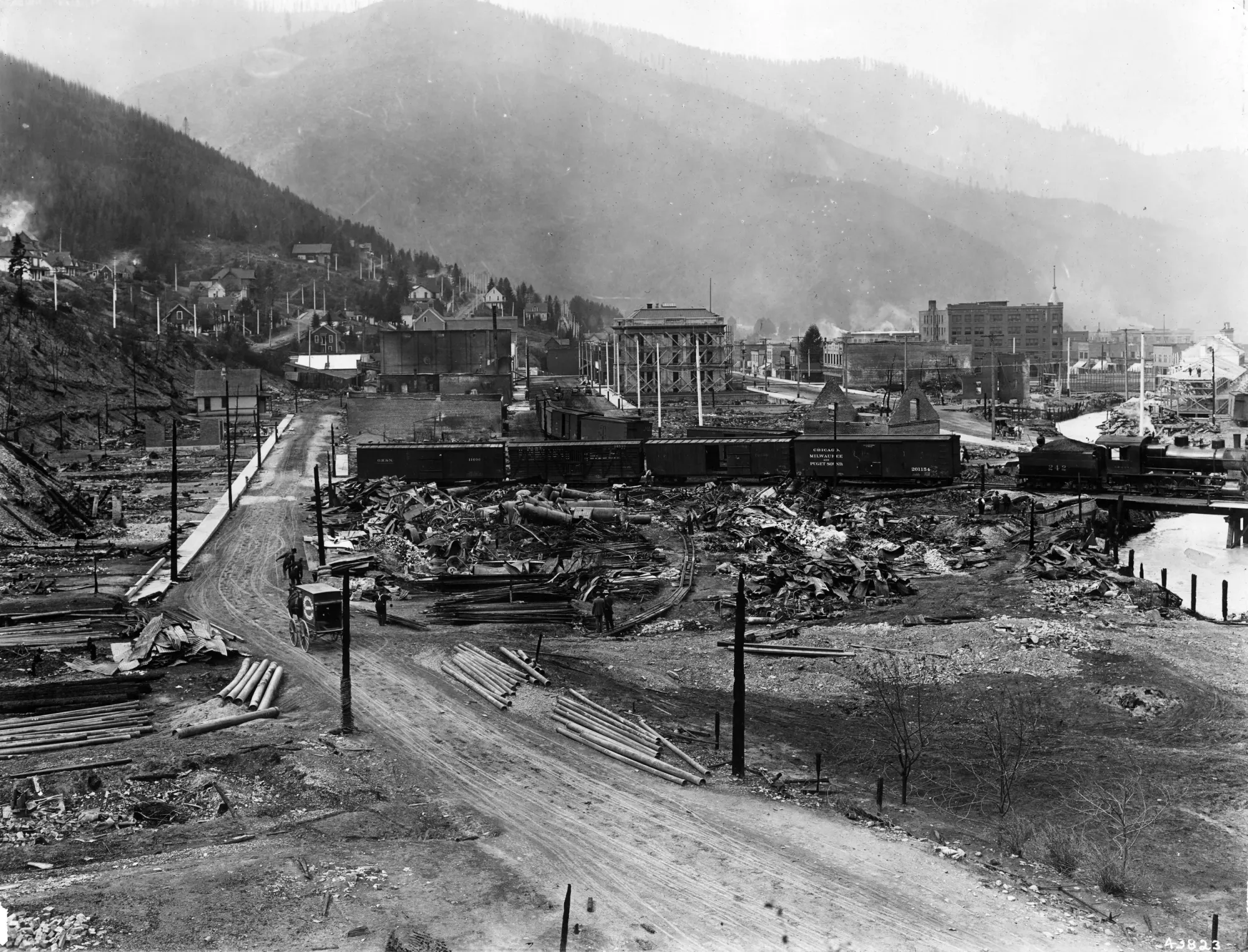

Six years later - August, 1910 – Greeley’s life was forever changed when hurricane force winds swept up the St. Joe River at St. Maries, Idaho, driving an estimated 600 slash burns and spot fires into a colossus that destroyed three million acres of mostly virgin timber in a 48-hour fire storm that killed 87 firefighters. Most of them were untrained and poorly equipped hobos recruited off the streets of Spokane, Washington. Some were even shoeless.

Most of Avery, Idaho was burned to the ground and half of Wallace was a smolderiing ruin. The task of identifying and burying the dead or shipping their charred bodies home fell to Greeley. He later said that the emotional shock put him on a path to “get converts” in Congress who would be willing to invest public money in fire protection and conservation.

Pinchot had been fired eight months earlier for insubordination by President William Howard Taft. He was furious – not at Greeley but at Congress for refusing to fund a firefighting corps within the five-year-old Forest Service.

“For the want of a nail, the shoe was cast, the rider thrown, the battle lost,” the flabbergasted Pinchot told a muckraking reporter from Everybody’s Magazine, a popular general interest periodical of that era. “For want of trails the finest white pine forests in the United States were laid waste and scores of lives lost. It is all loss, dead irretrievable loss, due to the pique, the bias, the bullheadedness of a knot of men who have sulked and planted their hulks in the way of appropriations for the protection and improvement of these national forests.”

Pinchot, who was never at a loss for words, founded the Forest Service with the help of President Teddy Roosevelt. He also famously floored Roosevelt in a boxing match at the New York Governor’s mansion in 1899.

“I had the honor of knocking the future President of the United States off his very solid pins,” Pinchot humorously said when asked who one the match.

TR was New York’s governor for two years before he joined President William McKinley in his 1901 run for re-election. McKinley won but was shot twice in the stomach at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo six months later by anarchist Leon Czolgosz. He died eight days later. Roosevelt was 42 when he assumed the Presidency and was elected to a full term in 1904.

President William Howard Taft, who was Roosevelt’s handpicked successor, in 1908, fired Pinchot amid his very public battle with Interior Secretary Richard Ballinger concerning coal leases in Alaska’s Chugach National Forest.

Despite his firing, Pinchot periodically acted as though he was still Forest Service Chief. He went on to serve two terms as Pennsylvania – 1923 through 1935 – but he bled Forest Service green until his death in 1946.

Following the 1910 Fire, Greeley returned to the Washington Office in 1911, the year after Forest Service Chief Henry Graves replaced Pinchot. Graves needed a new Chief of the Branch of Forest Management, so he picked Greeley, whom he had known since his years as Dean of the Yale School of Forestry. Nine years later Graves returned to his old job at Yale and Greeley was named Forest Service Chief on his recommendation.

Greeley and E.T. Allen, by then the Western Forest and Conservation Association’s first forester, were the driving forces behind congressional approval of the 1924 Clarke-McNary Act. Among other things, it put the Forest Service in the firefighting business alongside several privately-funded fire cooperatives established following the 1902 Yacolt Burn in western Washington.

Greeley and Pinchot had a long running and occasionally public battle over Pinchot’s belief that all privately-owned forestland should be federally regulated. Greeley disagreed, arguing in Some Public and Economic Aspects of the Lumber Industry, a 1917 paper in which he opined that cooperation, not regulation, was the better course of action for the federal government.

Pinchot was incensed. The “clear-cut” issue could only be resolved by the heavy hand of federal regulators. “The field is cleared for action and the lines are plainly drawn,” Pinchot argued in his all or nothing style. “He who is not for forestry is against it,” he avowed, arguing that Greeley had sided with lumbermen who were laying waste to the West’s forests.

It took Greeley more than four years to settle their score but he finally did within the Clarke-McNary Act. In addition to putting the Forest Service in the firefighting business, the Act established a federal-public-private partnership that remained the cornerstone of forest policy making in the United States until the federal government listed the Northern Spotted Owl as a threatened species in 1990.

A good case can be made for the fact that Greeley’s greatest contributions to forestry came after he resigned his Chief’s job in 1928 to accept the Executive Director’s position with the beleaguered West Coast Lumbermen’s Association in Seattle, then a major timber center in the West.

WCLA’s members were private timberland owners in western Washington and Oregon who were targets of Pinchot’s scathing criticism and his belief that their deplorable logging methods demanded federal regulation.

Greeley disagreed. Cooperation was key. WCLA’s members were abandoning cutover timberlands for which they had paid little because the risk of wildfire outweighed the cost of paying property taxes and replanting. Better to “cut and run,” leaving counties to deal with the environmental mess they had created.

In October, 1929, less than a year after Greeley left the Forest Service, the stock market collapsed and the nation fell into the abyss of a Great Depression that would last until December 8, 1941, the day President Franklin Roosevelt declared war on Japan, the day after the island nation bombed Pearl Harbor.

FDR had defeated incumbent President Herbert Hoover in a landslide in November 1932 on his promise to rebuild the nation’s shattered economy. But his belief that federal regulation provided the only pathway forward soon put him at odds with the private economy.

Nevertheless, Congress ratified his National Industrial Recovery Act three months following his election. Imbedded in it were “codes of fair competition” that gave FDR with power to suspend anti-trust laws, allowing businesses to self-regulate with his approval.

In due course, the Brooklyn-based Schlecter Poultry Company, which owned both a slaughter house and retail butcher shops, was indicted for code violations. In its landmark 1935 ruling, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Schlecter and against the President.

FDR was livid. The cornerstone of his New Deal – his vision for leading the nation out of the Great Depression – had been unanimously upended by the Court. In an opinion written by Chief Justice John Hughes, the Court ruled that Congress had unconstitutionally delegated its legislative authority.

Following his landslide 1936 re-election FDR confidentally proposed a new law that permitted him to nominate a new Supreme Court Justice whenever a sitting judge refused to resign at age 70. But the Democrat-controlled Senate Judiciary Committee was appalled by his “court packing” effort The measure was tabled by a 70-22 Senate vote in July 1936.

Bill Greeley saw real opportunity in FDR’s anti-trust codes. He proposed to WCLA’s leadership that they write our own codes and get FDR to endorse them. Surprisingly, they agreed.

On his train trip to Washington D.C. Greeley drafted codes that emphasized wildfire protection and reforestation – topics FDR thought were in his wheelhouse because he had paid for some some 500,000 trees to be planted at his family’s palatial Hyde Park estate on the Hudson River near Poukeepsie, New York.

“I am a forester,” FDR wrote when asked about his forestry credentials. He had none, so it was not surprising that he was thrilled with what Greeley and his WCLA leadership proposed.

It all came together under the aegis of the American Tree Farm System, founded by Greeley in 1941. Tree Farm No. 1 was the Clemons Tree Farm, a Weyerhaeuser Timber Company property near Montesano, Washington Greeley dedicated on June 12, 1941.

Gifford Pinchot died in Manhattan in October, 1946. He is buried in Milford, Pennsylvania, not far from Grey Towers, the Pinchot family estate now owned by the Pinchot Institute. Sadly, his bellicose instincts precluded his even mentioning Greeley in Finding New Ground, his engaging autobiography, posthumously published in 1947.

By contrast, the softer and more pragmatic Greeley always spoke diplomatically of Pinchot’s contributions to conservation. But it was he – not Pinchot - who quietly transformed the early Forest Service into the most influential and admired forestry organization in the world.

Here’s hoping the Forest Service’s twenty-first Chief, Tom Schultz, can breathe new life and vision into the politically battered and terribly demoralized agency.

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.