Bill Hagenstein's Prediction

Bill Hagenstein and I were friends for 43 years. He inspired my early interest in forestry. I first interviewed him

Last August 25, Noah Haggerty, a Los Angeles Times environment and science reporter, wrote a thought provoking essay titled, “To solve the wildfire crisis, we have to let the myth of ‘the wild’ die.” He is correct – and we could not agree more.

Haggerty’s epiphany came while he was hiking in Yosemite National Park, ground zero in the legendary May 17, 1903 discussion between conservationist John Muir and President Teddy Roosevelt. Muir sold the President on the uniquely American myth of the wilderness. It was an insult to Native American tribes that have been living in our “wilderness areas” for eons.

Increasingly, fire ecologists believe the myth is a primary cause of the wildfire crisis in the western United States. They are correct.

Haggerty writes that Muir believed Indigenous people had “no right place in the landscape.” Moreover, he had no tolerance for fire which he called, “the great master-scourge of forests.”

Muir was wrong – as are preservationists who still cling to the myth of the wild.

The truth is that Native Americans have been using fire to sculpt American landscapes from coast to coast for countless thousands of years. Fire was the only tool they had for clearing land to grow crops, attract game animals and create defensible space around their homelands.

The first person to report this was a scribe traveling with Spanish explorer and conquistador Hernando de Soto. After landing near present day Tampa, de Soto and his army marched north into Georgia, North and South Carolina, Tennessee, Mississippi and Louisiana in search of gold. None was found but de Soto’s scribe wrote that the army marched for about a week past one maize field.

Given fairly flat ground and a physically fit army, they could easily cover 10 miles a day. Probably more. Multiply 10 miles by seven days and you have a maize field that is 70 miles wide on one side!

Clearly, this field was the work of Native Americans who were very successful farmers – and fire was their only tool. No crosscut saws or chain saws and no mechanized logging equipment. Just fire.

Recently, archeologists in England unearthed a 400,00-year-old open air hearth buried in a clay pit. This discovery pushes back the timeline for fire-making by some 350,000 years. Whoever built the hearth had mastered the art of cooking food. Archeologists regard this discovery as a milestone in the advancement of social order.

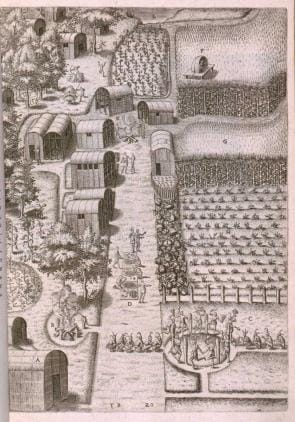

We first reported on tribal use of fire as an agricultural tool nearly 40 years ago. Pen and ink sketches of Native American farming in present-day Virginia illustrate row cropping that separated one crop from adjacent crops.

We also wrote about sophisticated irrigation systems in southern New Mexico and Arizona that rivaled Roman aqueducts. Transporting water from its sources to dry areas made it possible to farm - and live.

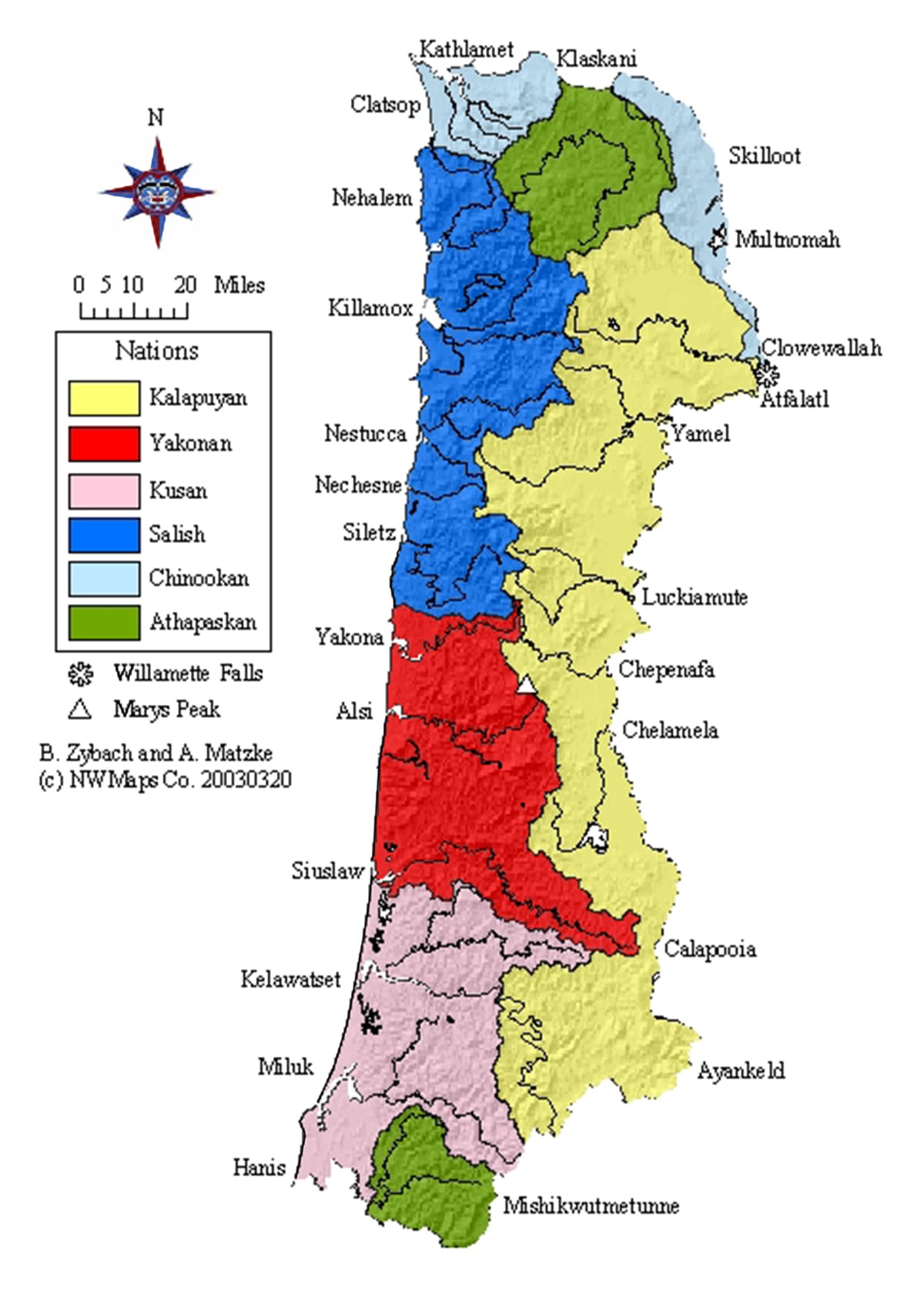

From coast to coast tribes used fire to clear land. Our colleague, Bob Zybach, has been writing about this phenomenon in western Oregon for decades. He continues to reject the notion of primal landscapes filled with old growth trees. So do we and so does the Coquille tribe, which claims 10,000 acres of ancestral land south and east of Coos Bay, including the 5,140-acre Coquille Tribal Forest.

Nationally, tribes from Grand Morias, Minnesota to Southern California and from Florida to Sedro Wooley, Washington own and manage about 19.2 million acres of forestland in 32 states. The 10 largest tribal owners manage well over half of this acreage using a variety of harvesting techniques in combination with prescribed burning to encourage native plants that attract birds and wildlife while also reducing the risk of catastrophic wildfire.

Tribes also use fire to protect their cultural and religious sites from wildfire. We saw thousands of these acres during the 40 years we worked with the Intertribal Timber Council. ITC represents the state and federal regulatory interests of more than 60 tribes.

Eons of plainly visible evidence tells us that we cannot stuff the Wildfire Genie back in her bottle until the myth of the wild is dead and gone.

Support Evergreen

Evergreen is supported by readers who value independent, science-based forestry reporting. Consider an end of year contribution.

(Donate or Subscribe)

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.