“Yes, the Gap Can Be Bridged"...USFS Chief, Tom Schultz

Wildfire has become the magnet among those who share our concern for the damage stand-replacing fires have done on public

Evergreen Foundation board member Dr. Peter Kolb is a world-class forest ecologist — and an avid deer and elk hunter. The photographs accompanying this post were taken by Kolb on the site of the 2007 Blackcat Fire, near his Missoula County home at the top of Evaro Hill a few miles south of Arlee, Montana.

The fire covered approximately 35 square miles, or nearly 12,000 acres. On one particularly active afternoon, a flank fire's rate of spread increased to approx. 1.3 miles per hour. Cost was estimated at approximately $21.6 million - $33.75 million today - making it one of the most expensive wildfires in Northwest Montana that year.

In the distance, the western larch have turned their signature fall gold. Every autumn they shed their needles, then flush neon green again in spring. This mixed-species forest is critical winter range. Deer and elk rely on it for both forage and shelter during the long northern winters.

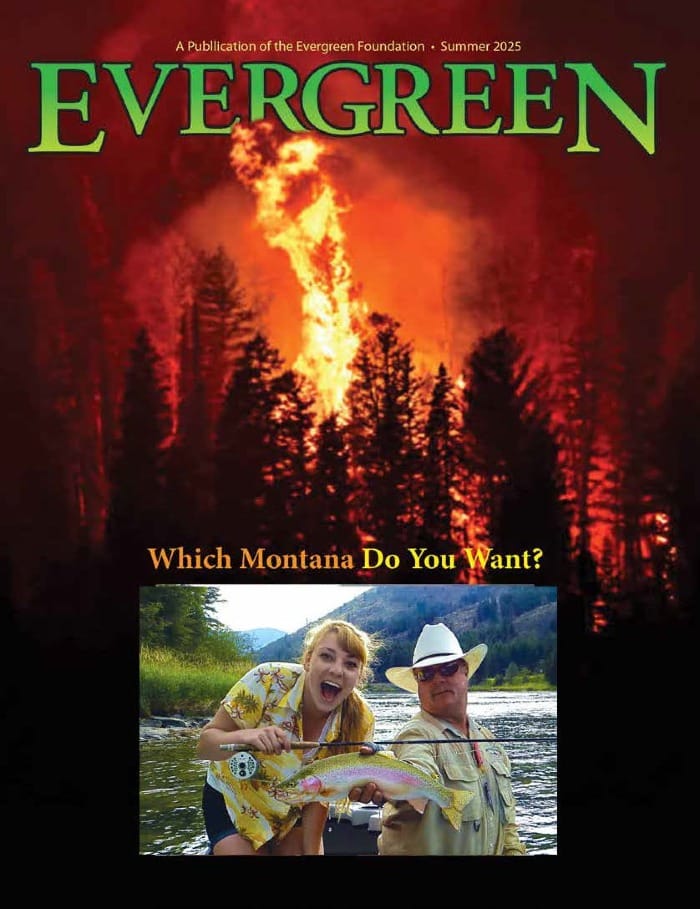

If this photograph unsettles you, it should.

Two forests lie side by side—one healthy and alive with deer and elk; the other choked, hazardous, and nearly unusable.

The difference isn’t mystery. It’s management.

Most readers don’t know that.

They don’t know why wildlife use one forest and avoid another, or why restoration lags on lands intended for public benefit. They don’t see how decisions in Washington, Missoula, and Libby shape the places they live, hunt, and raise families.

Public understanding doesn’t grow on its own. Evergreen grows it.

For 40 years, we’ve been the independent voice connecting science, stewardship, and community. If this work matters to you, we need you with us.

Reading isn’t enough.

Supporting the work is what keeps it going.

Reminder:

Our $10/month subscription option disappears in two weeks.

If you want to join at that rate, now is the time.

The forest visible in Kolb’s background photographs was managed by Plum Creek Timber Company, which acquired the tract in 1989 when Burlington Resources spun off 47 million acres originally granted to the Northern Pacific Railway in 1864. NP was one of six transcontinental railroads whose lines helped open the West to white settlement after the Civil War.

Plum Creek managed its former Burlington lands under a Master Limited Partnership until 1999, when it became the nation’s first timber-based Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT).

REIT status, with its “pass-through” structure, allowed profits to flow directly to shareholders at a reduced effective tax rate — leaving the REIT with little or no corporate tax obligation.

When the Plum Creek REIT merged with the Weyerhaeuser Company REIT in 2010, the combined company controlled 13 million acres. Yet that same year, they shuttered their long-standing plywood and lumber mills in Missoula, Kalispell, and Columbia Falls. Only one facility remains in Montana today: the former Plum Creek MDF (Medium Density Fiberboard) plant in Columbia Falls.

Larch has dominated western Montana forests for thousands of years, and it likely reseeded the Blackcat burn with ease. For more than a century it has also been one of the region’s most valuable timber species. Its high wood density makes it stronger than coastal Douglas-fir in both tension (overhead beams) and compression (wall studs).

Both species, however, are substantially stronger than other western softwoods — which is why big-box retailers often sell them intermixed in the same units of dimensional lumber.

Modern technologies increase their value even further.

Whether used as lumber, plywood, cross-laminated timber, or Mass Ply (a Freres Engineered Wood exclusive), laminated Douglas-fir and larch create exceptionally strong, stable structural materials.

The long-gone J. Neils / St. Regis / Champion / Plum Creek / Stimson mill in Libby served as northwest Montana’s economic anchor for more than 100 years. In its peak decades, J. Neils harvested roughly 50 million board feet annually, much of it larch from company lands.

Today, Libby’s last mill is Jeff Gruber’s HewSaw, located on Montana Highway 2. He buys logs from private landowners and custom cuts for anyone who walks in. His mill sits only minutes from the town’s Heritage Museum — itself built from logs supplied by the Libby Lumber Company more than a century ago.

Portland-based Stimson Lumber would like to build a modern high-speed small-log mill on the old J. Neils site, but the investment—likely $100 million or more—depends on the Kootenai National Forest being able to supply a reliable annual volume of timber.

Under the leadership of Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz, Kootenai harvest levels are increasing. That trajectory should continue now that the Kootenai National Forest and the Lincoln County Port Authority have finalized a Master Stewardship Agreement, allowing treatments in forests adjacent to the county’s vast Wildland Urban Interface (WUI).

Seventy-five percent of Lincoln County lies within the 2.2-million-acre Kootenai National Forest. The county’s 2023 Wildfire Protection Plan identifies 1,543,799 WUI acres, a figure that continues to rise as West Coast in-migration increases population pressure in northwest Montana.

Because they are essential to healthy forests and healthy communities.

When mills modify their equipment to process the small-diameter trees and overstocked material that must be removed to restore forest health, they become true partners in reducing wildfire risk and sustaining forest-to-community resilience.

Healthy forests need restoration. Restoration needs mills.

Modern mills built to use this material are what make thinning possible — and thinning keeps forests, wildlife, and communities safer.

Back to Kolb’s photograph: the area in the foreground is U.S. Forest Service land on the Lolo National Forest. It has not been managed in years. The result is a landscape choked with fire-killed trees and toppled woody debris — extremely difficult to traverse and, based on the absence of tracks, rarely used by deer or elk.

In contrast, the adjacent Plum Creek tract visible in the background — thinned, accessible, and regularly growing young forest — is heavily used by wildlife.

In 2008, using $500 million in congressionally appropriated Montana Legacy Project funds, The Nature Conservancy and The Trust for Public Land acquired 310,000 acres of Weyerhaeuser timberlands, including the Blackcat Fire tract. (The Plum Creek name was retired after the 2010 merger.)

Under Legacy Project rules, acquired lands are to be managed for recreation, “sustainable” forestry, and wildlife habitat.

Yet Kolb’s photo tells a harder truth:

The Blackcat burn still needs significant restoration work before it can meaningfully support deer, elk, or people.

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.