“Yes, the Gap Can Be Bridged"...USFS Chief, Tom Schultz

Wildfire has become the magnet among those who share our concern for the damage stand-replacing fires have done on public

Money doesn't grow on trees...

Our mission is public education as it relates to all things forestry - so your contributions matter. Your support means we can continue to bring you the quality of content you have come to expect from Evergreen.

If you appreciate our work, let us know - subscribe, donate, or leave us a tip!

On February 27, Tom Schultz was named the twenty-first Chief of the Forest Service. Many of my friends know Tom from his 14 years with the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation and his years as Director of the Idaho Department of Lands and, more recently, Vice President of Resources and Government Affairs for the Idaho Forest Group.

I know him best from his IFG years. We visited at several conferences in Boise. He is a big picture thinker who brings exceptional leadership skills to the Forest Service at a time when both are desperately needed. He possesses what Vice President George Herbert Walker Bush called “that vision thing” when a Time Magazine writer asked him if there would be an over-arching theme in his 1988 run for the White House.

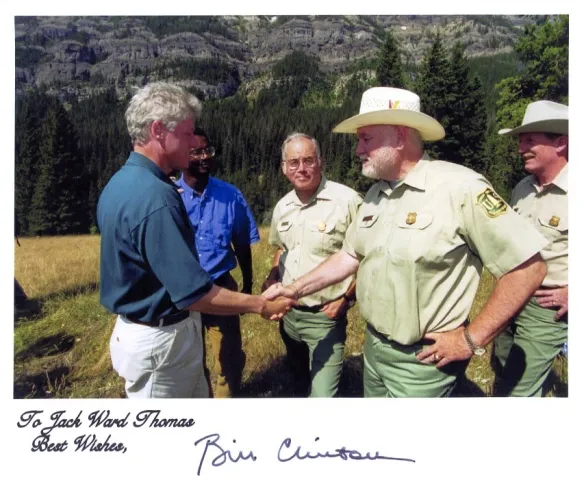

Schultz is only the third Forest Service Chief to be hired outside the ranks of the agency’s executive chain. The first was Jack Ward Thomas, an elk biologist in eastern Oregon before President Clinton picked him to lead the development of the controversial Northwest Forest Plan. He worked so impressed Clinton that he talked him into accepting the Chief’s post. The second was Mike Dombeck, a fisheries biologist, who was working for the Bureau of Land Management when President Clinton named him Chief in 1997, after Thomas resigned.

Jack and I got to know one another well during the years I was living in Bigfork, Montana. He had quit the Forest Service and accepted a Boone and Crocket-funded chair in the W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation at the University of Montana. I wanted to know why he quit. His answers led to many heated conversations at his home in Corvallis, Montana, but we remained friends. We had planned one last get together before cancer killed him. I still have the message he left on my cell phone a few days before he died.

Apart from his excellent book, Journals of a Forest Service Chief, Thomas has more than 600 articles to his credit: chapters in other books, essays and articles on everything from elk biology to land use planning. He was a strong advocate for zoning national forests based on eco-types. We have many of his writings in our library, along with dozens of books that trace the history of the U.S. Forest Service.

Of these books, the most comprehensive is Harold Steen’s book The U.S. Forest Service: A History. Steen held a PhD in History and was the Executive Director of the Forest History Society during its rise to prominence after Steen moved it to Durham, North Carolina in 1984.

The Forest Service also published several books of its own that chronicle its progress following its founding in 1905. Among them, 100 Years of Federal Forestry, aka Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 402, a picture book assembled by Forest Service retiree, William Bergoffen in 1976.

My personal favorites were written by Forest Service Chiefs who had lived their stories. These include Bill Greeley’s 1951 book, Forest and Men. Although he was Chief from 1920 to 1928, his book opens on the fire lines in western Montana and northern Idaho during the Great 1910 Fire, still the largest forest fire in our nation’s history.

Greeley was then the District Ranger for District No. 1 which included federal forests in western Montana, northern Idaho and northeast Washington. Among his post-fire responsibilities was the identification and burial of the 78 men who died in the three million acre conflagration.

The tragedy haunted Greeley for the rest of his life and had much to do with his significant behind-the-scenes role in ratification of the Weeks Act in 1911 and the Clarke-McNary Act in 1926. Clarke-McNary put the Forest Service in the firefighting business alongside a series of privately-funded cooperatives assembled by the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company following the 1902 Yacolt Burn. The fire leveled 239,000 acres of virgin timber in northwest Oregon and southwest Washington. Thirty-eight people were killed.

Greeley also wrote a lesser known book in 1953 titled Forest Policy, a three part compendium based on his years at the helm of the West Coast Lumbermen’s Association. He left the Forest Service to join the deeply-troubled association in 1928. He had concluded that WCLA was in dire need of a major course correction that would align it with Forest Service reforestation and conservation interests.

Gifford Pinchot's Breaking New Ground also well worth reading. It was published by his estate in 1947, the year following his death. The Forest History Society published Jack's Journals in 2004.

Both men were held captive by political events of their time. With Pinchot it was wildfire and his belief that regulation was the only way to control the harvesting excesses of private forestland owners. With Jack it was the northern spotted owl and wildlife habitat conservation.

President Theodore Roosevelt named Pinchot the first Chief of the Forest Service at its founding on February 1, 1905. They had been friends and confidants since Roosevelt’s years as New York Governor. On that same day, Roosevelt signed the Transfer Act, moving 63 million acres of designated Forest Reserves from the scandal ridden Department of the Interior to the newly formed Forest Service. About 500 employees answered to Pinchot.

Those 63 million acres were in Forest Reserves designated by Presidents Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland – most of them in the West.

Tom Schultz’s Forest Service includes 154 national forests, about 30,000 mostly demoralized employees and 193 million acres. About 180,400,000 of these acres are located in 84 National Forests in the West and about half – some 93 million acres– are dying, dead or burnt to a crisp.

I have been flooded with questions from worried westerners who want to know what Schultz thinks or how he might tackle the mess he faces. My guess is that he will first hire a Washington Office staff he trusts, then he will turn his attention to the regulatory impacts of the Supreme Court’s Chevron Deference ruling. More on this in a moment.

We are fortunate to already know a few things about Schultz’s 30,000-foot view of the Forest Service and its tattered relationships with states, counties, and stakeholder collaborative groups because he joined three other big picture thinkers who were asked to pen their thoughts in an essay that appeared in 193 Million Acres: Toward a Healthier and More Resilient U.S. Forest Service, a 2018 book published by the Society of American Foresters.

Their essay was titled Cooperative Federalism, Serving the Public Interest: A Policy Analysis of How the States Can Engage Local Stakeholders and Federal Land Managers to Improve the Management of the National Forests.

Schultz’s co-authors were Holly Fretwell, then a research economist with the Property and Environment Center [PERC] in Bozeman, Montana, Dennis Becker, then Director of the Policy Analysis Group within the University of Idaho’s College of Natural Resources, now Dean of the College of Natural Resources and Kelly Williams, a natural resources lawyer and Adjunct Professor at the S.J. Quinney College of Law at the University of Utah.

The essay is long, but it will tell you what Schultz and his big picture colleagues saw when the looked at the struggling Forest Service eight years ago and asked themselves what could be done to help the agency get back on its feet again.

It seems inconceivable to think that Schulz ever thought the task of rescuing the Forest Service would fall to him - but he is now at the helm of a shell-shocked agency that is in real danger of tumbling off the crumbling cliff it has occupied since the federal government added the Northern Spotted Owl to its list of threatened species in June 1990.

There is no point in rehashing the history of how the world’s most admired natural resource management agency became one of the most reviled.

Terminate the Forest Service’s Overreaching “Managed Fire for Ecosystem Benefit” Policy

This is one of the most controversial, perplexing, and misled practices the agency has embraced in its 120-year history.

The concept of "managed fire" as a standalone approach is misleading - as it neglects the crucial need for regular thinning and prescribed burns under the right conditions - to restore balance to our overstocked public lands.

New Mexico’s 2022 Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak Fire is a prime example. It started as a prescribed burn on long-neglected land, despite conditions being too windy and too dry—directly contradicting the Forest Service’s own guidelines for a "managed burn."

The fire quickly escaped its handlers. Some 341,400 acres and several hundred homes were burned.

Taxpayers have thus far paid more than one billion dollars in damage claims. This recurring scenario across the West continues to leave devastation in its wake.

How much more destruction must occur before the Forest Service's reckless "managed fire" practices are abolished?

Chief Schultz can do it in a heartbeat with his own executive order aimed at forest-to-community health - a holistic, mutually inclusive approach to management, stewardship, ecosystem stabilization, and conservation.

Decades of scientific studies support the necessity of periodic thinning and prescribed burning in overstocked forests. When evidence-based science is applied, there is no safer or more cost effective way to reduce the risks associated with insect and disease infestations - and inevitable wildfire.

Just ask our First Nations citizens—they successfully managed the land long before science recognized the wisdom of Indigenous knowledge.

States, tribes, and private landowners regularly thin and burn to reduce biomass, manage debris, improve soil health, promote a healthy forest ecosystem, improve tree propagation, and mitigate insect and disease infestations. The Forest Service once did the same, but after the spotted owl was listed in 1990, it abandoned these practices. Too often now, the Endangered Species Act is used as an excuse for inaction.

Recasting the Wrecking Ball: Reforming the Equal Access to Justice Act

The EAJA was created to help ordinary citizens stand up to the government overreach, but elite environmental groups have hijacked it into a weapon for their own agendas.

Well-funded organizations, backed by wealthy donors, file endless lawsuits - to block responsible forest management.

They claim to be committed to justice, but they exploit a law meant for the underprivileged, forcing taxpayers to pay for their legal battles.

They claim to fight for conservation, yet their legal obstruction to thinning and prescribed burns has led to more devastating wildfires, insect infestations, and diseased forests.

The EAJA must be reformed to ensure our forests are managed with science - not endless litigation that hurts communities, damages our forests, and squanders public funds.

Reform will take time - but until it is done - all of the current Administration’s forestry-related executive orders will be challenged by serial litigators. This is an ongoing cycle, regardless of the administration - because they risk nothing.

While Congress is unlikely to exempt federal lands from the EAJA, it could replace litigation over forest plans with binding, baseball-style arbitration.

In this process, serial litigators and stakeholder collaboratives would each present their case, and arbitration judges would determine which proposal best aligns with the goals and objectives of the disputed forest plan.

Some experienced advisors suggest that the Equal Access to Justice Act could be improved through executive orders that reverse specific changes made during the Clinton Administration.

These modifications, introduced long after Congress originally passed the Act during the Reagan years, expanded its misuse - allowing well-funded groups to exploit taxpayer dollars for endless litigation.

Restoring the EAJA to its original intent through executive action could help curb these abuses and ensure the law serves those it was meant to protect, rather than elite litigators and obstructionist organizations.

Return to Evidence-Based Forest Service Culture

A profound cultural shift is underway within the Forest Service, driven by a sharp decline in the quality of forest science education at U.S. universities.

This decline stems from universities prioritizing federal research funding tied to political agendas, leading to an education system that promotes selective science rather than comprehensive, evidence-based forestry practices.

Decentralize the Forest Service's Organizational Structure

Decision-making about our public lands must shift away from Washington and Regional Offices and return to District Ranger Offices. Local staff—who understand the land, have community trust, and can foster collaboration—are best equipped to make informed decisions.

However, given shifts in education and experience, some Ranger Districts may need support. Recent Forest Service retirees and qualified mentors can help by completing essential NEPA documents, including Environmental Impact Statements, Environmental Assessments, and Categorical Exclusions.

Jack Ward Thomas likened NEPA’s regulatory process to a 'Gordian Knot,' suggesting it was nearly impossible to navigate without facing lawsuits - lawsuits often used as a delay tactic to stall timber salvage after wildfires.

However, successfully navigating NEPA without litigation is possible. A retired Forest Service expert on our Evergreen Foundation Board has done so multiple times.

With intention and a commitment to collaboration, we can reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire, disease, and insect infestations while maintaining environmental balance and strengthening the connection between forests and communities.

Align Forest Service Regulations with New CEQ Standards Under the Supreme Court’s Chevron Deference Decision

In Loper Bright Enterprises v Raimondo [Gina Raimondo was the Biden Administration’s Secretary of Commerce from 2021 to 2025] the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Loper Bright, a New Jersey Fishing Company that sued the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Chevron Deference was established in 1984 by the Supreme Court in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. Justices ruled for NDRC, requiring lower courts to defer to the agency’s interpretation of a statute if the statute was ambiguous. Justices assumed that the agencies were experts in their subject matter areas and that Congress intended for the agencies to fill in gaps in statutes.

By a 6-2 margin the Roberts-led Supreme Court overruled Chevron Deference, citing the 1946 Administrative Procedures Act. APA spells out the process that federal administrative agencies must use to propose or establish administrative laws or regulations. It also grants federal courts oversight over all agency actions.

The upshot of the Loper Bright Enterprises v Raimondo ruling is that CEQ - the Council of Environmental Quality - must now revisit and revise decades of federal regulatory overreach involving federally-owned natural resources.

To wit: Jack Thomas’ Gordian Knot.

Once CEQ finishes its work, it will be Chief Schultz's job to lead the same effort within the Forest Service. My guess is that he is up to his eyeballs in this process.

CEQ’s draft regulations are expected to be released soon. A 30-day comment period will follow, then a 45-day timeframe for implementation. It will be Chief Schultz’s responsibility to bring Forest Service regulations into alignment with new CEQ standards.

What we have here is a significant opportunity to loosen the “Gordian Knot” by adding much needed efficiency to the National Environmental Policy Act,

NEPA has become a tangled mess after 40 years of improper court rulings and excessive agency regulations. However, the Supreme Court’s decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo has undone much of this bureaucratic overreach, providing an opportunity to restore clarity and proper implementation of the law.

The Supreme Court has shredded the litigation-based business model that opportunists and obstructionists have relied on to push a false narrative about public land management.

They only make money if the public believes that conservation and management are mutually exclusive - that any form of active management is harmful - and that humans cannot play a responsible role in maintaining balanced ecosystems.

Chief Schultz is going to need his own chorus - composed of conservationists, forest scientists, stakeholder collaborative groups - everyone who enjoys the environmental and economic benefits that flow from well managed forests...

Clean air, clean water, abundant fish, bird and wildlife habitat and the very long list of year-round outdoor recreation activities that can only be found in healthy, thriving forests.

As I’ve said before but it bears repeating...

It’s time to saddle up and ride hard. We have a long way to go and a short time to get there.

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.