Going on Faith

From Wild Bill Hagenstein to the Big Bang, a reflection on curiosity, science, and belief. A Question from a Reader.

Many Oregonians do not understand or appreciate the statutory role timber growth and harvest from state-owned forests have played in rural school funding for more than 160 years. Here is a short primer.

The federal government awarded Oregon 3.4 million acres of Public Domain Land when it became a State on February 14, 1859. At that time, Congress was actively promoting capital investments in budding communities and economies in the West.

Per the state constitution and subsequent legislative action, these acres were placed in a dedicated trust, known as the Common School Fund, that is still in force today. The fund distributes harvest revenue to schools and other units of county government that lay within the forest.

Managing these lands is the responsibility of a three-member State Land Board [SLB] that includes the Governor, State Treasurer, and Secretary of State, respectively and currently Kate Brown, Tobias Read, and Shemia Fagan.

Over time, a significant amount of this 3.4 million-acre award was sold, traded and/or logged for the benefit of schools. The 91,000-acre Elliott was designated in 1930 as a means of consolidating scattered parcels in exchange for about 70,000 acres of the Siuslaw National Forest south of the Umpqua River.

The Elliott held about 4,000 acres of merchantable timber in 1930 - not enough to support a profitable timber program. But the soils on this forest are among the most productive on Earth, so by 1955 - the year the Oregon legislature turned the forest over to the Oregon Department of Forestry [ODF] - the forest was growing about 75 million board feet annually.

It was an enormous timber treasure. So much that if ODF had been able to start cutting that much annually in 1955 – which it didn’t – it could never have caught up with annual growth.

But at that time, the Elliott that laid beyond those 4,000 merchantable acres was mostly covered with Douglas fir and red alder trees that seeded themselves after several large fires, including the 1879 "Big Burn," plus subsequent decades of livestock grazing, firewood gathering, logging, and clearing fires set by early settlers, including the Gould’s and McClay’s referenced in the main story.

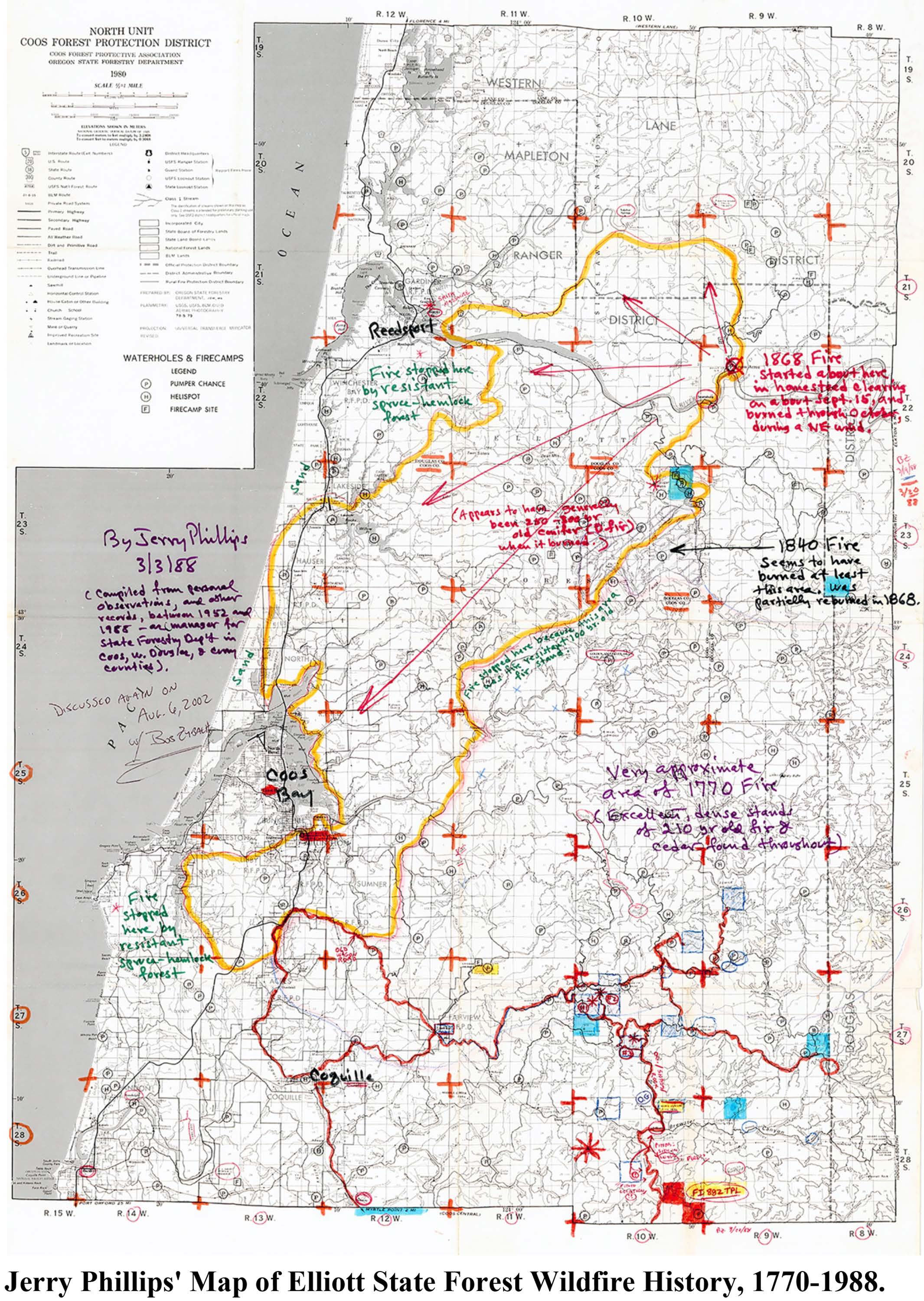

The Jerry Phillips map is a good approximation of the detectable fire history of lands that became part of the Elliott.

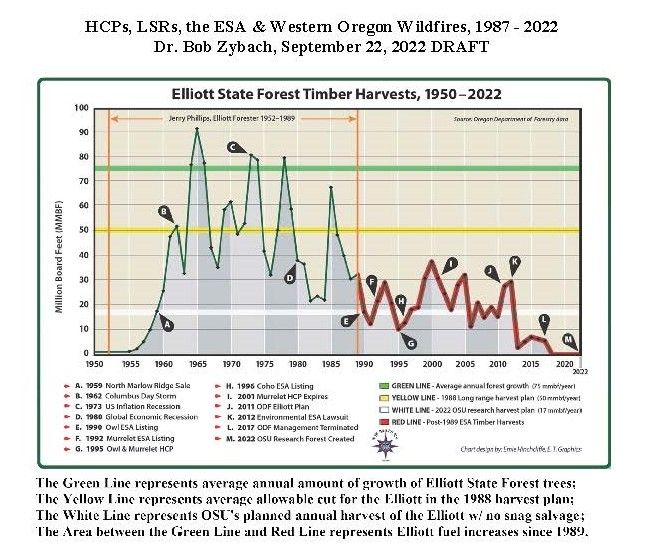

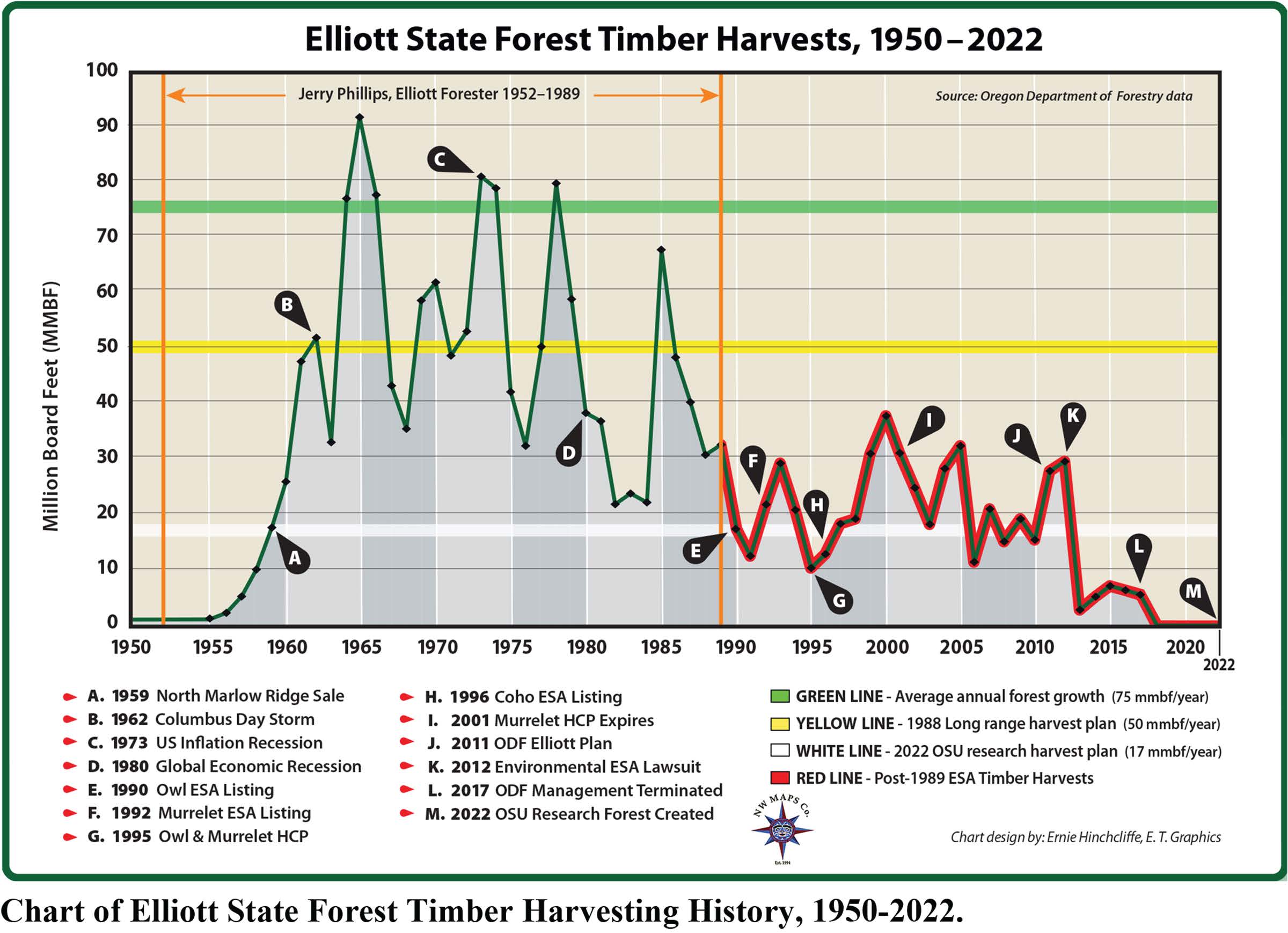

And this graph that tracks the pivotal role Jerry Phillips played during the 37 years he worked on the Elliott, nearly 20 as its manager.

The history leading to his time on the Elliott is worth summarizing because many Oregonians have no idea what they had or what they’ve surrendered in the name of “protecting habitat” for Spotted Owls, Marbled Murrelets and Coho Salmon. Before lawsuits transformed the Elliott into a money-losing proposition, it's timber generated millions of dollars that funded county schools and other units of local government.

Jerry was transferred from his job as Coos District logging inspector to the Elliott staff in 1956 and was soon assigned the task of inventorying timber volume of the Forest. The inventory would be used to identify timber ready for harvest that could be sold to fund road construction - the goal being to develop a sustainable timber growth and harvest program for the Common School Fund.

The first major logging sale on the Elliott was a stand of mostly 200-year-old Douglas fir on North Marlow Ridge [See the letter “A’ on the nearby graph]. Log hauling started on April 22, 1959, and a photo of the event appears on the front cover of Jerry's Elliott history.

Then, on October 12, 1962, everything changed. The Columbus Day Storm [See the letter “B” on the graph] swept over the Elliott without warning and blew down 100 million board feet of 70-year-old second-growth timber. Winds exceeding 150 miles-per-hour were recorded.

The next several years were devoted to building more than 200 miles of road needed to reach 250 areas filled with toppled trees that had to be recovered while they still had value. Jerry served as sales coordinator on more than 300 timber sales completed over the next six years. In those six years, annual harvest from toppled trees increased by about 11 million board feet. But remember, the Elliott was still growing some 75 million board feet of new timber annually.

Jerry was promoted to the Elliott manager’s job in 1970, and in 1984 he was named "Oregon Forester of the Year" in recognition of his excellent work as a forester and as manager of the Elliott under unprecedented circumstances - and for the Forest's subsequent, and significant, economic contributions to the Common School Fund and to local communities.

The graph tracks the increasing and decreasing harvesting between 1970 and 1984. Note the impacts of the 1973 [C] and 1980 [D] recessions.

In 1988, the Elliott adopted a long-term annual harvest plan average of 50 million board feet based on the Forest's continued growth and Jerry’s continuing success managing natural and human events. He retired the following year and the year after that – 1990 - the federal government listed the northern spotted owl as a threatened species and the Elliott’s 1988 plan was shelved. [See E].

Two years later [1992] the Marbled Murrelet, a sea bird that sometimes nests on large limbs in old growth Douglas fir, was listed. [ F] and in 1995 spotted owl and Marbled Murrelet habitat conservation plans [HCPs] were released. [G] At this point, the Elliott’s annual harvest stands at 10 million board feet – about where it was in 1955 and the Forest continues to grow about 75 million board feet annually.

In 1996 Coho salmon are granted federal listing [H] and the Elliott harvest stands at 18 million board feet, about where it was when the North Marlow Ridge Timber sale was sold in 1959. [A]

In 2001, the Murrelet HCP expired [I] and in 2011 [J] the state issued its new Elliott Forest Plan. Between 2001 and 2011, harvesting rose to 30 million board feet [where it was in 1960], then fell to about 10 million [where it was in 1959] then rose again to about 29 million in the year the new Elliott plan was released [2011].

The following year [2012] a coalition of environmental groups – Portland’s Audubon Society, Eugene’s Cascadia Wild and Tucson, Arizona’s Center for Biological Diversity sued the State of Oregon, alleging that its new plan was illegal. They won. Logging jobs on 28 active sales in State forests were halted.

Over the next six years [2012-2018] Elliott harvesting fell from 30 million board feet per year to zero – where its stands today. But the Forest continues to grow at least 75 million board feet annually, which will be problematic as it forest density increases, inviting insect and root rot infestations and subsequent wildfire.

This disease and wildfire problem appears on the graph as the area between the red and green lines since 1990. The OSU white line leads directly to a predictable and largely preventable result.

Rather than contest the court’s ruling, the Governor and the SLB decided they would sell the Elliott at a fraction of its former value. When this sale was ruled illegal, they transferred ownership to OSU for research purposes, terminating ODF’s decades-long management role. [L] When this transfer was also ruled illegal, the 2022 Oregon State legislature voted to rename the Forest as the Elliott State Research Forest, with OSU responsible for its management.

Interestingly, the OSU plan has been publicly criticized by Jerry Franklin and Norm Johnson, a duo that has been significantly involved federal forest/Spotted Owl/Marbled Murrelet/salmon-related issues since the 1980s. Here is their assessment of the proposed plan:

"The current document puts the cart before the horse by proposing a major experiment before conducting such an analysis and without developing on-the-ground familiarity with the property.

"In addition, the experiment OSU has proposed is badly flawed, compromises development of the long-term research potential of the forest and lacks significant relevance to management of Oregon’s forests.

"The proposed experiment violates basic principles essential to production of statistically valid and socially convincing outcomes. Furthermore, the focus on Triad, an academic concept related to land allocations at regional scales, has no relevance to pressing forestry issues facing Oregonians."

Remaining tasks the State Land Board must complete before it can decouple the Elliott from its legal obligations to the Common School Fund include developing a new HCP. OSU also needs to develop a functional operating plan - and then the search for funding for research operations can begin.

Editor’s note:

Bob Zybach and I have been friends and colleagues for more than 30 years.

He first appeared on the cover of Evergreen Magazine in 1994 in a rousing essay in which we questioned the underlying old growth assumptions that helped form the basis for the 1990 spotted owl listing.

Nearby is Bob’s touching remembrance of Jerry Phillips, a forestry legend in Oregon and the guiding force behind management of the Elliott State Forest for more than 30 years. I never met Mr. Phillips, but I know he was one of at least six rock-solid mentors who helped Bob navigate his Master’s thesis and PhD dissertation at Oregon State.

I knew four of them well: Wayne Giesy, Bob Buckman, Mike Newton and Ben Stout. All four are gone now, most recently Mike, who was an Evergreen Foundation board member for many years. We have separately posted our remembrance of Mike. Here,

Wayne’s Giesy Plan, which he developed with Bob’s help, is still the only rational approach I’ve seen for conserving the Pacific Northwest’s federal forests in ways that minimize the risk of devastating wildfire.

Bob Buckman was a world-class forest scientist with a jaw dropping Rolodex. I last interviewed him two years before his death in 2016. He said something so memorable that I can still quote it verbatim. “I will argue that for every dollar spent studying late succession forests a dollar should be spent studying early succession.”

Ben Stout and I became friends during the spotted owl wars. Like Buckman, he had a Rolodex to kill for. It was he who introduced me to Hugh Raup’s writings, which we are now featuring in a series of essays on this website. Hugh was a world-renowned field botanist and a legendary boat rocker in academic circles. Think Bob Zybach.

Now, Bob’s essay...

In Memory of Jerry Phillips: 1927-2022

Jerry Phillips passed away in March, while vacationing with his family in California. He was 94 years old and had lived a long, productive, and mostly very happy life. Jerry was widely known for most of those years as a highly successful forester and as a truly "good man."

For as long as there will ever be an interest in Oregon's first State Forest, the Elliott, there will be an appreciation of Jerry Phillips. He was the Forest's most accomplished manager in its history: a fact clearly recognized by his professional contemporaries and well documented, as Jerry was also the Elliott's most accomplished historian.

Jerry lived the Elliott’s history for a good deal of his professional life. His written**,** and recorded archives have been the basis of several significant research and educational projects undertaken following his retirement. Most of this work is housed at Oregon State University [OSU] Archives and accessible at ORWW.org. I expect students and researchers who are interested in the Elliott’s history will use it for decades to come.

In 1984 Jerry was selected Oregon State Forester of the Year in recognition of his successful management of the Elliott and in 2000 he was elected a Fellow of the Society of American Foresters [SAF], a national honor bestowed on him partly in recognition of his comprehensive 1997 history of the Elliott – Caulked Boots and Cheese Sandwiches: A Forester’s History of Oregon’s First State Forest.

SAF’s Oregon Society is the largest in the nation. There are 15 chapters and 800 members. In most years, the Oregon group might select one or two “Fellows” from its membership roster for “long-standing service to forestry at the state, local and national levels,” so Jerry’s selection was a significant recognition of his long career and high standing among his peers.

In 2019, the Oregon State legislature designated a stand of Elliott old-growth as "The Jerry Phillips Reserve.” He had been instrumental in securing the 50-acre tract from the old Weyerhaeuser Timber Company in the 1970s. Local humorists had dubbed the land exchange “Jerry Phillips Private Reserve,” a play on the Henry Weinhard’s Private Reserve beer label – and his contemporaries were soon calling him “one of the first environmentalists.”

In the true meaning of the word, Jerry was an environmentalist, a fact that helps explain why SAF’s Oregon members honored him with their "Lifetime Achievement Award" last year.

Jerry appreciated all of the awards and recognitions that followed him into retirement, but he was a humble and unassuming man who never sought public recognition for his work. And forestry wasn’t the most important thing in his life. When his daughter Sally called to tell me he had died, she remarked that her father "had truly loved God, his family, and the Elliott - in that order."

Jerry was one of the two or three most Christian people I have ever known. I knew him for 35 years and David Gould, his lifelong friend, knew him for nearly 70. In all that time neither of us had ever heard him swear, become angry, say something mean about anyone, or fail to be calm, kind, and helpful whenever he could. Not a typical forester.

Neither of us had ever heard Jerry say a prayer or preach, either. If you asked, he would say he was a Christian, and maybe the name of his church, but that was about it. My impression was Jerry wouldn't shy away from a discussion of religion -- but wouldn't necessarily initiate one, either. Over time, David has often said that Jerry became his "hero" and was his "role model." Actions speak louder than words.

I only learned the great importance religion played in Jerry's life in the past few weeks, following his death and after reading his unpublished 2009 autobiography and self-published 2003 family history. I also learned he was an amateur ham radio operator, an accomplished choir singer, a musician, a sharpshooter, and a typist. I knew his academic and professional histories fairly well, knew he drove local veterans to the hospital in Roseburg and back every week for many years, into his 90s, and think I heard he taught Sunday School at times -- but everything else was a revelation, and in some detail.

Jerry describes his father: "I was so blessed to have had him as my father. He was a good role model -- had clean speech, good manners, and I never knew him to smoke or drink. He did not talk about it, but I believe he was a Christian -- who, with my mother, regularly attended the Multnomah Presbyterian Church, a little west of Portland."

The Multnomah church and congregation were so important to Jerry's family that even after moving to their new home in "Powellhurst," east of downtown Portland and a one-hour drive each way for his father -- they continued attending Sunday services there for seven or eight more years. That, in addition to a six-day work week and chores, such as milking the goats, gathering eggs, and weeding the garden. As the two older Phillips boys began classes at Franklin High School in 1942, the family moved to the much-closer Mt. Tabor Presbyterian Church.

World War II was winding down when 18-year-old Jerry enlisted in the Marine Corps, so his service was limited to 15 months. In his unpublished autobiography he wrote that those months were "the longest time I ever lived without attending church."

By the time he got home, Jerry’s parents had enrolled him at OSC, now OSU. He was soon a regular member of the Corvallis Presbyterian Church. He sang in the church choir, same as always, but was also a member of the 38-voice Corvallis Men's Choir, which performed such four-part harmonies as "The Lost Chord," "Goin' Home," and "All Through The Night."

Jerry met LaRose Bowman, his future wife of 60 years, on a blind date during that time. LaRose was also an OSC student but attended Corvallis Methodist Church. When they married, following Jerry's graduation in June 1950, it was in the Methodist Church, but due to circumstances, was officiated by the Presbyterian minister!

Following LaRose's graduation and a variety of short-term forestry jobs, Jerry accepted work with the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF) in 1952, in Coos Bay. The young couple, with baby Sally, moved to their new home that year and stayed the rest of their lives. For the next 36 years the Phillips family -- including four sons that followed Sally -- were members of First Methodist Church, where Jerry sang in the choir and taught Sunday School for 23 years.

In 1988, after raising all five children in the Methodist Church, Jerry and LaRose moved to Hauser Community Church and stayed there the next 30 years. Within a few years the Hauser congregation had grown to 1600 members and became the largest church in Coos County.

Near the end of his 2003 self-published family history and genealogy, on pages 176-179, Jerry directly addressed his "ten Grandchildren (and generations to follow)." These pages are a detailed summary of his religious beliefs, titled The Author's Own Personal Faith Statement. It is basically a clearly and sincerely written nine-point outline of timeless Christian lessons -- and most likely a distillation of Jerry's many years teaching Sunday School and leading Bible studies. For his descendants.

Jerry was definitely a family man. He and LaRose raised their five children in the Coos Bay home they built in 1959, and both lived in until the end. LaRose, the love of Jerry's life, died in 2010. His two younger brothers, each with four children of their own and numerous grandchildren, survived him; as have four of Jerry and LaRose’s children, their "ten Grandchildren" and now, 10 great-grandchildren more.

Jerry's father, Jim, died relatively young and unexpectedly at age 59. His mother, Georgia, lived to be 92. From the time the Phillips family moved to their home in Powellhurst in 1934 until she remarried and moved again in 1975, Georgia lived in the family home. Her three sons graduated from high school there, and they, their wives, and ultimately her thirteen grandchildren, always celebrated Thanksgiving and Christmas at "Grandma's." In later years the milk goats and chickens had disappeared, but there was always a large, beautiful garden and lots of flowers.

Education and music were very important in the Phillips household. Jim had an OAC [Oregon Agricultural College, now OSU] degree in Animal Husbandry and Georgia had been one of the first female graduates of Stanford, in 1922, with a degree in history.

The Phillips sons also earned college degrees as did all five of Jerry and LaRose's children. According to daughter Sally, they were never asked "if" they were going to college, but "where?" It didn't matter what courses they took, but after graduation the question became whether they were "finding employment, or not."

Jerry and his brothers learned band instruments in high school, and Jerry sang bass in church choirs for many years. After the kids were born there were weekend and annual camping vacations around the State, and even trips to the Grand Canyon, Washington DC, following the Oregon Trail, and other distant locations.

While hauling their tent trailer behind the family car, "Mom and Dad" would pass the travel time by singing songs, such as "She'll Be Coming Round The Mountain," "America The Beautiful," and other favorites. Sometimes the kids would sing along; all five played band instruments in high school, of course.

After devoting the first seven years of his retirement researching and writing his history of the Elliott State Forest – an epic 414-page documentary self-published in two editions and 300 copies -- Jerry turned his attention to his own family history. He then spent the next seven years researching, writing, and self-publishing Our Phillips Family.

As might be expected, Jerry's genealogical research was exhaustive. To his and LaRose's pleasure it involved a lot of domestic and overseas travel. “Like most of the Phillips family [Jerry] “did not 'inherit the math gene'," but he was able to trace the Phillips name and family in North America back to 1676 and the arrival of indentured Welsh servants, George and Mary Phillips. Despite his lack of “the math gene” Jerry determined that – counting his own grandchildren – the 10 generations totaled 77,644 descendants by 2003!

In contrast, Jerry's mother's family, the Thompsons, had both emigrated to North America from Denmark in the 1890s, met and married in Oregon, and owned a wheat farm in Moro that is still in the Thompson family more than one hundred years later.

Jerry worked there two summers as a teenager during the War.

One of Jerry's earliest memories was of his father driving the family to a ridgetop in west Portland to view "a terrible, throbbing red glow in the sky many miles away" -- the catastrophic 1933 Tillamook Fire. He was seven years old.

When he was 16 – and still too young to serve in World War II - Jerry got a job with the U.S. Forest Service on a 15-man fire crew near Cave Junction, in the Siskiyou National Forest. "By the end of the summer" he was "hooked" and had "subconsciously chosen my life career -- as a professional forester."

The following year, 1944, Jerry was given the task of manning the Chetco Peak Lookout Tower, located in today's Kalmiopsis Wilderness and then only accessible by a 17-mile pack trail. Because it was still wartime, he was also trained to identify the silhouettes of Japanese warplanes and to keep a constant vigil for them, as well as for forest fires.

Jerry graduated from high school, turned 18, and joined the Marines as WW II was ending. Just as his ham radio skills had aided his work with wildfire fighting crews, his high school typing classes allowed him to complete his service as an office worker in Hawaii. His skill with a rifle meant an extra $5/month pay and all added to the G.I. Bill. God's grace.

By the time Jerry returned home, his parents had already enrolled him at OSC**,** no time off, as he had wanted and expected. He majored in Forest Management and spent summers working as a fire lookout. His permanent 1952 ODF job in Coos Bay started as a "Compliance Inspector" for "Coos District" logging and sawmilling operations, which included the Elliott State Forest.

In his Elliott history, Jerry wrote that he’d been “vaguely aware of the Forest’s existence since attending OSC**,** where it was described in college literature as an undeveloped State-owned forest of young timber lying between Coos and Umpqua Rivers, dedicated to educational purposes."

At the time, the Elliott was only accessible by 1930s Civilian Conservation Corps roads, foot trails, and pack trails, many established and maintained by early pioneers, including the Gould and McClay families beginning in the early 1880s.

One of Jerry’s earliest encounters on the Elliott was with Glae Gould, a hard-nosed fourth-generation Coos County resident who supported his family in the 1950s as a contract logger, sawmiller, road builder and quarry rock salesman. As a taxpayer, Glae considered it his right to call Jerry at any time of the day or night to resolve a problem. Jerry always answered and did his best to help.

Glae’s 10-year-old son, David, was working with his father on a salvage logging job on Elliott property about a mile from the Gould family sawmill. David worked on the log landing, unhooking logs from their choker cables, setting tongs on log trucks and bucking root wads with an unwieldy Homelite chainsaw with a 32-inch bar.

Enter Jerry Phillips with an order for the crew to stop logging because they didn't have the correct number of fire extinguishers on the job. Glae's rapid fire response was to yell and swear at Jerry, who remained calm. Then the two of them jumped into Glae's war-surplus Jeep and drove "straight downhill on a Cat road, with Jerry hanging on for dear life" to the sawmill, where they picked up the required number of fire extinguishers and returned to work. Problem solved.

I met Jerry for the first time March 3, 1988 at his home on Kingwood Avenue in Coos Bay. His wife LaRose was a gracious hostess. They had raised their five children in this hilltop house they had designed and built together, 30 years earlier.

I was a middle-aged forestry student from OSU, conducting Oregon Coast Range wildfire history research under Professor Dick Hermann; Jerry was the widely acknowledged expert on the topic for Coos County; and we both had a strong interest and common history in Douglas fir forest management and reforestation. Memory says we had previously only talked by phone or corresponded on these topics.

The focus of discussion was Jerry's hand-annotated fire history map of the Elliott. He had drawn it for me earlier that day. The map and subsequent discussions became an important part of my PhD research and, also for the next three decades, at the center of our ongoing discussions of spotted owl politics and Elliott Forest planning.

Jerry retired the following year, at age 62. Clark Seeley, Klamath Falls District Forester, who had started his career as a "Forester Trainee" on the Elliott, replaced him:

Jerry later wrote that, “Four pairs of spotted owls had been observed in our Mill Creek canyon when I walked out the front door of our Coos Bay Office on my last day of work, May 31, 1989, so things were looking a little bit ominous (even though "experts" said owls required old-growth)."

For the next seven years Jerry focused on researching and writing the history of the Elliott State Forest, which book he considered "almost another of my children."

In June, 1990, the federal government added the presumably old-growth dependent northern spotted owl to its list of threatened species. Many owls had been located in Elliott second growth stands as young as 60 years. Save for the 50-acre tract that Jerry had acquired in the 1970s through a land trade with Weyerhaeuser, there was no old growth on the Elliott. and scattered logging remnants over 1,000 acres on Mill Creek, along the County Road to Loon Lake.

No one would have blamed Jerry had he voiced bitterness over the government’s decision to include the Elliott in its listing decision. Others certainly did and many still are, but Jerry never did. What he did say several times was that he found great irony in the federal and state decisions to manage the Elliott “for the birds” rather than Oregon’s schools and school kids. I discuss this in a nearby sidebar story about the Elliott.

In the summer of 2017, Jerry, David, Wayne and I toured the Elliott and discussed possible strategies for implementing a new forest plan that might pass muster with the court of public opinion – an essential first step given Common School Fund obligations that can only by met by growing and harvesting Elliott timber in perpetuity.

The four of us settled on a strategy aimed at building public understanding of the issues behind the court-ordered shutdown of the Elliott’s forest management program and the state’s decision to sell the forest. We were soon spending a lot more time together on the Elliott, recording oral histories based on Jerry's book. These recordings and indexed transcriptions are now part of OSU Archive’s "Elliott State Forest Collection."

David funded a "Jerry and LaRose Phillips Endowment" for forestry students at North Bend High School. The 2017 recipient was one of Tasha Livingstone’s students, so we contacted Tasha, the forestry instructor on the Coos Bay campus of Southwestern Oregon Community College, to gauge student interest in studying the Elliott’s history and possibilities. Tasha readily agreed to spring-term field trips to the Forest and the related development of a draft recreation plan - a first for the Elliott.

Jerry, David and I led these field trips - five or six a year – with Jerry’s book and oral histories as our guides. His death leaves a hole in the program but plans are already in place for 2023. David and I led this year’s tour and will do it again next year.

The 2020 COVID pandemic forced us to videotape what would have occurred on the field trip. These recordings – which feature David and Jerry - are posted on ORWW’s YouTube channel for student and public use. David also funded development of a permanent ORWW educational website for SWOCC and OSU forestry student use. Students can now share their research with one another and interested publics.

Jerry contracted pneumonia earlier this year. Sally and granddaughter Shasta nursed him back to health. He lost some weight but was strong enough to take a few drives through the Elliott with David. He was looking forward to his California vacation. He died there at peace and with family. Age 94. A wonderful life exceptionally well lived. His life’s work will continue through the intellect and energy of hundreds – if not thousands – of aspiring foresters to follow.

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.