Going on Faith

From Wild Bill Hagenstein to the Big Bang, a reflection on curiosity, science, and belief. A Question from a Reader.

—Yogi Berra, watching Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris hit back-to-back home runs for the Yankees in the early 1960s.

We’ve used that line here many times to describe the wildfire crisis that began unfolding in the West after the Clinton Administration listed the Northern Spotted Owl as a Threatened Species in 1990.

Many westerners believe the listing decision was based on phony data. We don’t know that for certain.

What we do know is this: Ed Green, a PhD statistician at Rutgers University, dismantled the statistical reliability of the owl population data. We know it because we have a copy of Green’s report.

That report never saw the light of day.

Why? Because Jack Ward Thomas, who directed the Interagency Spotted Owl Committee, threatened Green’s untenured academic career. Thomas later admitted this to us—reluctantly—in the final years of his life. He died in 2016.

To understand the connection between the owl listing and today’s wildfire crisis, readers should spend time with a remarkable essay written three years ago for Forest History Today, published by the Forest History Society.

The author is Doug MacCleery, a 60-year member of the Society, a longtime Evergreen contributor, and a friend for decades.

His essay—The Role of Indigenous People in Modifying the Environment of the Pre- and Post-Columbian Southeast U.S.—could just as easily have been written about the Far West, Midwest, Southwest, or Northeast.

The bibliography alone speaks volumes.

The LANDFIRE vegetation habitat map at the beginning of MacCleery’s essay (top of the page) tells two closely related stories:

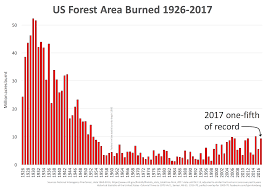

The graph that follows was intended to show how the federal government corralled wildfire after the disastrous 1910 Fire, the largest in U.S. history.

But it also tracks something else:

the disappearance of prescribed burning rooted in Indigenous Fire—and the rise of larger, more frequent, and deadlier wildfires following the Northern Spotted Owl listing.

Active forest management—thinning and burning—came to a halt.

MacCleery documents Indigenous Fire practices that shaped forests coast to coast for millennia.

Those practices were recorded by early European expeditions, including Hernando de Soto, who landed in Tampa Bay in 1539. His diarist described Indigenous use of fire to clear land and grow crops.

This was America’s first déjà vu story.

It repeated season after season—until European smallpox and the federal government’s disastrous reservation policies followed the Civil War, often to mask treaty violations.

We know that treaty story well in our house.

Julia’s father, Wes Rickard, was at the forefront of multiple federal trials that resulted in more than six billion dollars in settlements for tribes whose treaty rights had been violated by the government.

The loss of frequent, low-intensity burning—Indigenous Fire—is a primary reason why more than half of the nation’s 193 million acres of federal forestland is dying, dead, or burned to a crisp.

That reality collides with the enduring Myth of the Wild.

States and private landowners who use thinning and tribal burning techniques have far healthier forests. It’s also why hundreds of rural western communities—many located in federally designated Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) areas—remain at risk under federal management.

We see real reasons for hope in the Trump Administration’s stated intent to reverse decades of politically driven forest policies that followed the 1990 owl listing.

Next week, we’ll be interviewing Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz. Wildfire—and the policies shaping it—are high on our list.

Stay tuned.

Support Evergreen

Evergreen is supported by readers who value independent, science-based forestry reporting.

(Donate or Subscribe)

Your 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.