Midweek Musings...Stay curious!

Curiosity, Connecting the Dots, and the Work of Stewardship I have written several articles that touch on the value of

The Trump Administration plan for reorganizing the U.S. Forest has ignited a political firestorm.

No one should be surprised. President Trump is easily the greatest political fire starter in our nation’s history. He enjoys it – and it’s a cheap and easy way to gauge public opinion.

We do our best to stay out of the political weeds but the misrepresentation of so many issues tied to the environment, conservation, forest science and climate change challenges us daily.

Many observers – us included – were shocked by the Trump Administration’s decision to take a pickaxe to the Forest Service’s budget.

It still shocks us but no more than the Biden Administration’s determination to push the Forest Service over a fiscal cliff as a favor to its anti-forestry supporters.

The Trump Administration seems to believe that the only way to fix the Forest Service is to tear it to shreds and start over.

Some have voiced their fear that the agency could be isolated within the Bureau of Land Management, one of several divisions within the Department of the Interior.

We don’t believe this will happen. It’s more likely that the Forest Service will be reorganized in a way that bypasses most of the traditional functions of its nine Regional Offices.

On-the-ground decision-making will be pushed down to the District Ranger and Forest Supervisory levels – where it resided for decades and frankly - where it belongs.

On-the-ground decisions should not be made at the Regional level or, worse, the Washington Office. Many in Washington DC have never seen the forests over which they've held absolute control since the 1980s.

This centralization of decision-making authority is the reason why more than half of the 193 million acres in Forest Service care are dying, dead or burnt to a crisp.

At this writing it appears that some 2,600 Washington-based positions will be consolidated in five regional hubs: Salt Lake City, Utah; Fort Collins, Colorado; Indianapolis, Indiana; Kansas City, Missouri; and Raleigh, North Carolina.

The clock is now running on a 30-day public comment period that ends August 26. We hope you will add your voice to what promises to be a lively discussion.

USDA Opens Public Comment Period on Department Reorganization Plan

The Forest Service’s public lands ownership surrounds hundreds of small resource-based communities in the rural West that were destroyed in the wake of the Northern Spotted Owl listing in June, 1990. No measures were taken to create a resiliency plan to help these communities cope with the loss of their economic base. None.

a

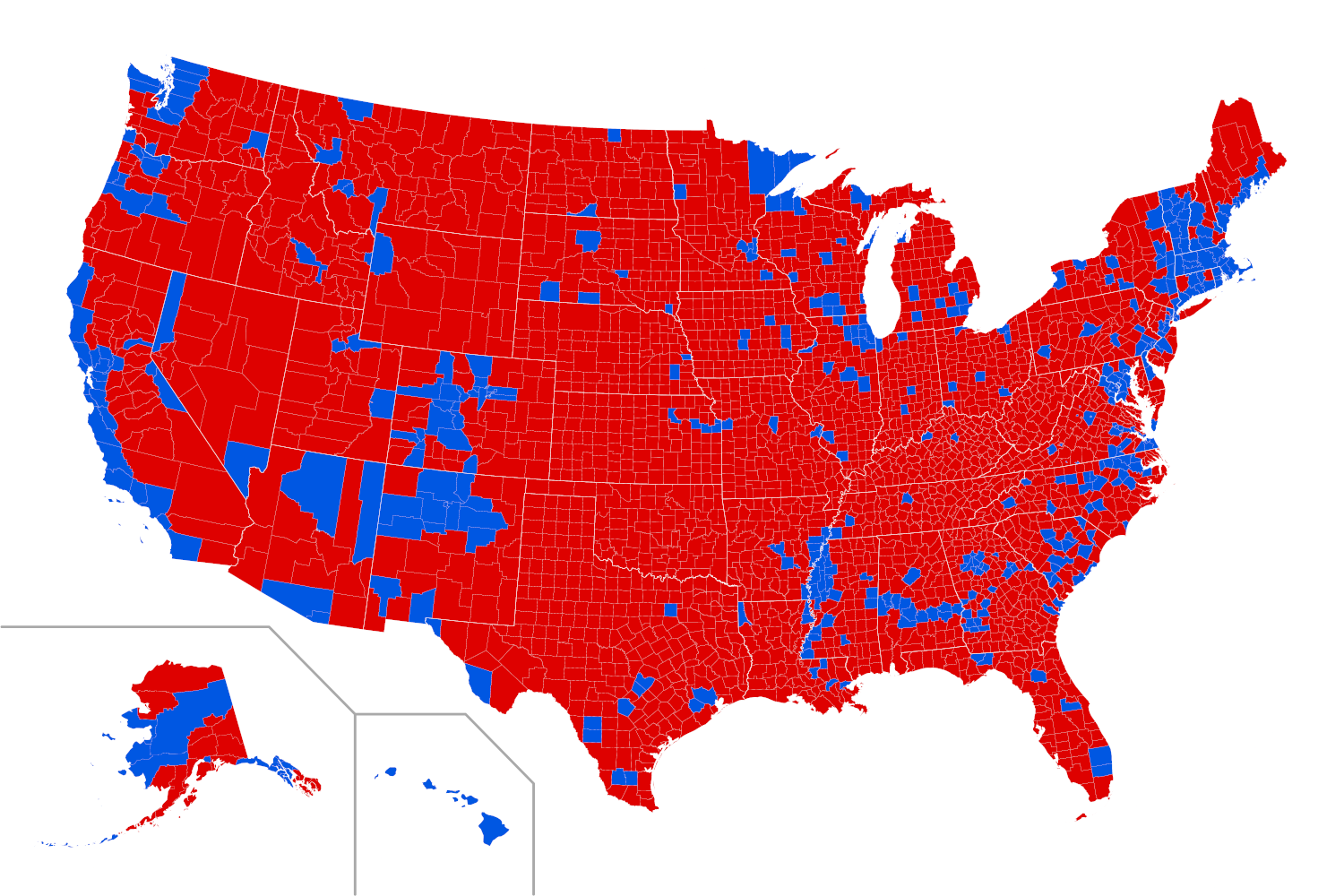

Translation: one's rural cultural, environmental, and economic values don't matter - it became an assault on all that identified a community - as a community. So the pendulum swung hard. The above map tells the story. Save for the more populous blue areas the entire West voted for Trump.

This isn't about whether you like the president. It is about the result of choices made and pushed - by one faction - without consideration for the effect on the whole. It is what happens when we try to separate people from the land and human beings the enemy.

Many in the rural West will - understandably - express their anger, frustration, and grief during this legally required public comment period.

Hundreds of small communities that relied on the forest for their livelihood have never recovered. Increase in crime, addiction, teen pregnancy, school dropout, domestic violence, drug trafficking and production, addiction, government assistance. Loss of community infrastructure - fire, law enforcement, city government, businesses, schools, jobs, population. More miles for work, more miles to mills, severe wildfire on the rise - say goodbye to carbon sequestration.

Most devastating was the exit of hope - and the loss of resilience - in the community and the forest.

Those who are used to controlling the narrative are losing their grip on a forest policymaking process they have controlled for decades. I suspect they and their Washington DC lobbyists will spend millions of dollars in defense of what they believe to be their moral high ground. We will see how that plays out.

This seems like an opportune moment to ask whatever happened to all of the planning documents the Forest Service, Natural Resources and Environment [NRE], a branch of the Government Accountability Office, and the National Association of Forest Service Retirees [NAFSR] have prepared since 2021.

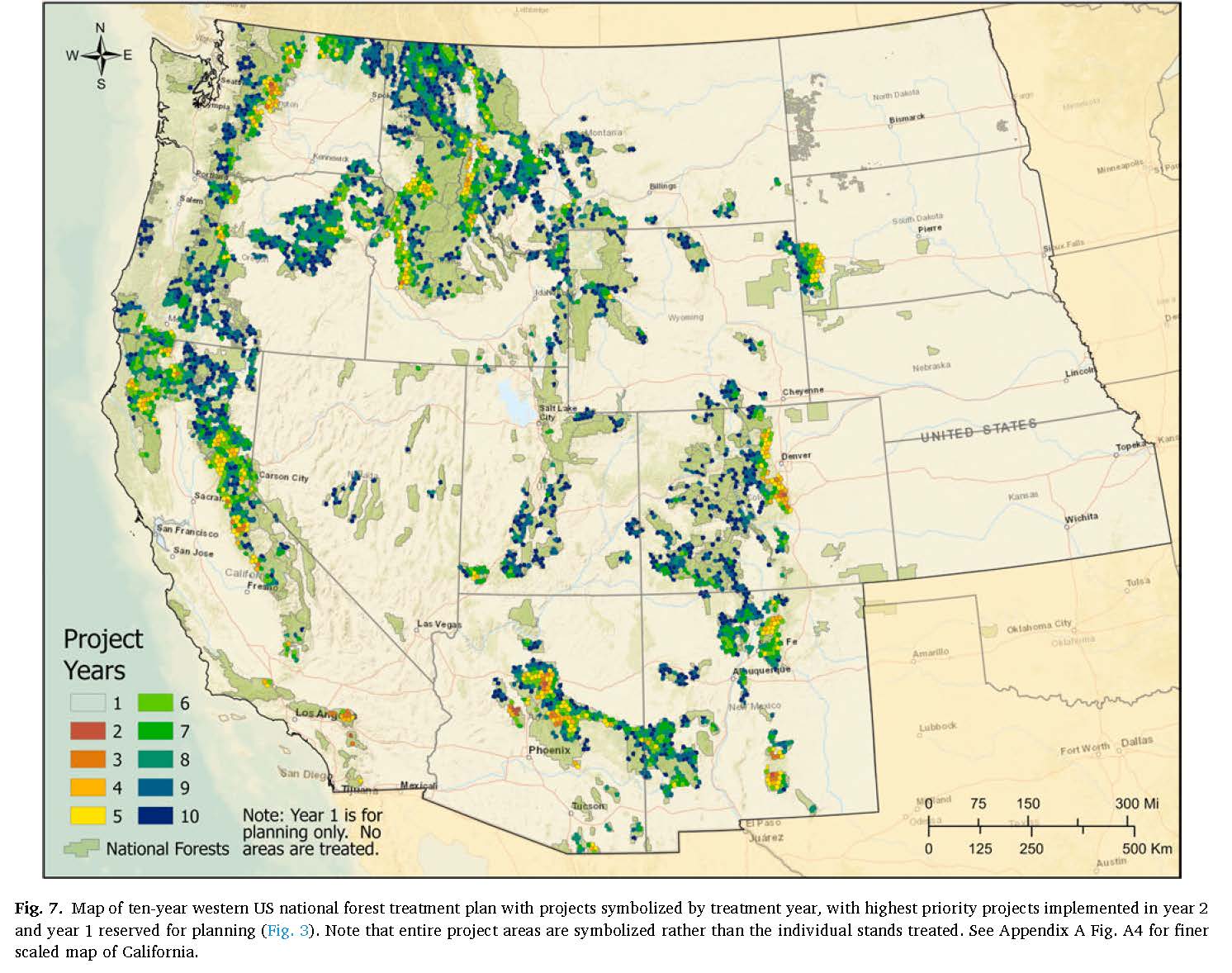

NAFSR’s 2021 position paper – America’s Forest Management Crisis, A National Catastrophe, laid out the problem and its solution in four pages plus a color coded map of proposed treatment areas covering years 1-10. Never happened.

NRE monitors federal efforts to protect air and water quality for GAO. It laid out the problem and its solution in 4.5 pages, but one of those pages is a full page map of high-risk fire sheds and another page includes a large table that quantifies FY 20-22 progress in 10 high risk areas. Not much progress yet.

In Confronting the Wildfire Crisis the Forest Service needed 45 pages to explain its strategy. The January 2022 report is beautifully photographed with lots of charts, graphs and footnotes that document what needs to be done to rescue National Forests from insects, diseases and wildfire. Little progress.

The agency updated its 2022 report in a very readable 2025 assessment that spans 15 pages and describes outcomes – thinning and prescribed burning – that aren’t possible until Congress musters the courage to put side boards on the Equal Access to Justice Act.

Look no further than Montana to see the damage anti-forestry groups and their lawyers have done by deliberately misusing the Act’s intent and purpose.

Tree mortality exceeds growth in nine of 10 National Forests in Big Sky Country. The net loss [growth minus mortality] is north of 1.41 billion board feet.

Timber harvesting in Montana has declined 80 percent since the University of Montana Bureau of Business and Economic Research [BBER] published its first timber industry report in 1972.

The late Maxine Johnson, a BBER economist, assembled the report at the request of the Montana State Department of Planning and Economic Development. It focused in sawmilling and logging income and employment - factors much on the minds of elected state government officials because forest management the more isolated Treasure State trailed other western states following World War II.

Some Montanans view the near collapse Montana's logging and wood processing industries as good news. We don’t. There are well-documented links between science-based forest management and the health and vitality of forests.

But it would be inaccurate to singularly blame the timber industry 's problems on serial litigators and their anti-forestry cohorts.

Montana’s lumbermen and loggers ought to be actively involved in explaining the environmental benefits that accrue when forestry and logging are byproducts of forest stewardship.

This is the message that Montanans who are worried about the loss of aesthetic values in their forests need to hear and see for themselves.

These values include what we call "The Big Four."

We first heard them expressed by randomly selected participants in focus group sessions hosted by pollster Frank Luntz during the runup to House and Senate approval of the Healthy Forests Restoration Act, signed into law by President George W. Bush in December 2003.

We’ve been discussing these values on this website and in Evergreen, our quarterly magazine, for 22 years:

Clean air

Clean water

Abundant fish and wildlife habitat

A wealth of year-round outdoor recreation opportunity.

The Big Four benefit from the Adaptive Forest Management applications we’ve been exploring more recently in association with our grizzly habitat restoration project.

These applications have become forestry art under the stewardship of Chad Oliver, a Pinchot Chair Emeritus at the Yale University School of the Environment. He is one of 16 partners in our project, now in its third year.

Oliver holds a PhD in Forestry and is one of the world’s leading authorities on forest stand dynamics. He studied under the late David Smith, a PhD silviculturist who pioneered the study of forest stand dynamics in the 1950s.

Stand dynamics focuses on the underlying physical and biological forces that constantly shape and reshape forest ecosystems. It refutes the long held belief that forests existed in a state of perfect balance.

Legendary Harvard University botanist Hugh Miller Raup blew perfect balance to smithereens in Forests in the Here and Now, published by the Montana Forest Conservation Station in 1981 and edited by our late friend and colleague, Ben Stout, who was named Dean of the Montana School of Forestry in 1978.

Our grizzly project's use of stand dynamics principles is a good example our forestry education outreach, though a botanist at the Rocky Mountain Research Station – another partner – told us we have in tow is a botany project because it involves developing food sources for grizzly bears...because bears don't eat trees.

Early evidence suggests our stand dynamics thinnings can double as travel routes that help grizzly bears circumnavigate rural communities in western Montana and on the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountain Front.

Many school playgrounds in these regions are protected by tall chain link fences topped by coils of razor-sharp concertina wire. Residential garbage cans and roadside dumpsters are frequently torn apart by hungry grizzlies.

Until we get the grizzly science right, there is zero chance that we’ll be able to practice what we’ve learned about the bears on the Kootenai National Forest. It holds at least 500,000 acres of overstocked timberland that needs to be thinned before it burns - the "management" regime preferred by anti-forestry activists.

Unfortunately, what’s left of Montana’s wood processing industry sees no benefit in Evergreen’s forestry education outreach because it believes the results can’t be measured in board feet. This isn’t true, but what’s left of the industry continues to whistle past its own graveyard.

In Which Montana Do You Want? we explain the environmental benefits of what tribes call "Indian Forestry." Native Americans didn’t have chain saws - so they used fire to create open spaces where they grew legumes, herbs, fruits, nuts and berries and browse and wild grasses for food, clothing, and utilitarian items, and to attract the animals they hunted.

Adaptive forest management uses techniques that replicate the practices of our First Nations. Thinning is done by creating natural fire mosaics - by applying frequent, low impact fires.

These light burns shape multiple layers of diverse wildlife habitat - while reducing the risks of catastrophic stand replacing wildfire in federally designated Wildland Urban Interface in Montana. WUI's often contain hundreds of homes.

QR codes in this well photographed and illustrated report lead to publicly funded source material, related articles and publications, legislative actions, an outstanding field guide, and hundreds of research reports some dating from the 1930s.

It’s all digital, so you can easily share our report with friends, family, colleagues, community groups, educators, elected officials...and don't forget to reach out to those who may not understand that we CAN and MUST make management and conservation a mutually inclusive dynamic.

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.