The Schultz Interview: What We Are Hearing...

As of this morning — our February 3 interview with Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz has generated more than 600 responses

Editor’s Note: Sales of First, Put Out the Fire! have been brisk. Several readers have offered “what comes next” suggestions that add substance and clarity to our book. To that end, we are featuring articles that continue to develop the themes set forward in our book.

Last week, our article Blowtorch Forestry profiled Frank Carroll’s blistering criticism of current Forest Service firefighting practices. He believes the agency is illegally allowing big wildfires to run in hopes of achieving the same environmental benefits that “managed fire” can deliver when planned well in advance.

This week, we are featuring an interview with Brett L’Esperance, CEO and one of the owners of Dauntless Air, an aerial firefighting company that recently moved its maintenance facilities to Pappy Boyington Field, about 15 minutes from our home here in Dalton Gardens, Idaho.

Dauntless and Mr. L’Esperance appeared on our radar screen last January, about the same time First, Put Out the Fire! went to press. Air Attack, a New Zealand magazine that showcases aerial firefighting technology, published an article by our colleague, Mike Archer [Wildfire News of the Day] titled “Rapid Initial Attack: The Wave of the Future?"

Within days, we found a second article in FIRELINE, a publication of the National Wildfire Suppression Association, written by L’Esperance and titled “Five Ways to Avoid Wildfire Destruction in 2020."

Days later, our copy of SMOKEJUMPER, the National Smokejumper Association’s quarterly magazine arrived. It’s cover story, “Save a Billion Dollars a Year: The New Fire Triangle," written by Managing Editor, Chuck Sheley, builds on the Air Attack and FIRELINE essays.

All three essays add significantly to the body of work contained in First, Put Out the Fire! So, too, does Dauntless Air’s vision paper and a PowerPoint presentation. L’Esperance and his staff developed it to document their company’s quite successful partnership with the Washington Department of Natural Resources.

Now, please enjoy “Yes, Mr. Sheley, this is how it’s supposed to be.”

I know this because it took me years to realize that the events that form stories often take weeks – and sometimes years - to develop. Forests and forestry have been my beat – the focus of my writing - for 35 years. So, you’d think I’d have all the story-lines down pat…and you would be wrong. If this craft teaches nothing else, it teaches patience and humility.

The cacophony of voices questioning Forest Service misuse of “unplanned ignitions” [blowtorch forestry] in service to “managed fire.” The meticulously planned use of fire to restore natural resiliency in fire adapted forests that have grown so dense that they invite insects, diseases and, eventually, fire itself.

Landscape and fire ecologists are constantly in the hunt for remote locations where they can safely pre plan and test their assumptions about the natural role that fire plays in ecosystem health and species succession.

Even under ideal conditions, “managed fire” is controversial because of the attendant risks to air and water quality, fish and wildlife habitat, and of course, the public’s forest playground. The Forest Service has added layers of confusion and suspicion in its failing attempt to achieve “managed fire” goals - by simply allowing “unplanned ignitions” to run their course.

Blowtorch Forestry, last week’s post on our website, recounts Frank Carroll’s experience with Forest Service misuse of unplanned ignitions. Carroll and his business partner, Van Elsbernd, advise law firms representing clients who are suing the Forest Service for damages done by unplanned ignitions. Ignitions that got away from firefighters, incinerating private forest plantations. We have been made aware of several such incidents in Idaho and Montana.

I interviewed Carroll after he wrote to say he enjoyed reading First, Put Out the Fire! but he wished I had brought the story forward another 20 years to include unplanned ignitions. Me, too, given the enormous response to the interview. Lots of very constructive suggestions for where “the story” goes from here.

Production work on my book was already well underway when I began to see stories in other publications that told me my story was about to charge off in a new and unanticipated direction – like an unplanned ignition gone astray.

It began with two essays – one in Air Attack, a New Zealand magazine that profiles innovations in aerial firefighting and a second in FIRELINE, a publication of the National Wildfire Suppression Association, which is run by Debbie Miley, who I have known for about 30 years.

The FIRELINE story, “Five Ways to Avoid Wildfire Destruction in 2020, was written by Brett L’Esperance, CEO and one of the owners of Dauntless Air. More on that in a moment.

L’Esperance’s key point in his FIRELINE essay is that current federal wildfire policy and suppression strategies are “crippling our country’s initial response system.” Response times are thus falling far short of the speed at which wildfires race through dead and dying timber stands choked with woody ground debris.

To speed initial attack – key to keeping fires small and contained – L’Esperance suggests a new approach involving the deployment of aerial assets capable of reaching fires in a matter of minutes, not hours.

Embracing what L'Esperance calls “a military mindset” would save lives, property and forests at far less cost to the government and insurance companies, allowing taxpayer dollars to be shifted from firefighting to forest management activities designed to restore natural resiliency in fire adapted forests. I discuss restoration forestry at great length in First, Put Out the Fire!

The Air Attack story was written by Mike Archer, a Los Angeles copywriter and the brains behind Wildfire News of the Day, a Monday thru Friday news feed we hold in high regard. Mike’s story was based on his separate interview with L’Esperance concerning Dauntless Air, a Minnesota-based company that flies 13 amphibious Single-Engine Air-tankers [“Fire Bosses”] equipped to fight forest fires.

Unlike the lumbering MD-87’s, RJ-85’s and BAE-146’s [Large Air Tankers or LATS] that the Forest Service prefers, “Fire Bosses” can be deployed in remote locations – small towns that are surrounded by national forests - and flown from crude airstrips – a meadow will do- much like their crop-dusting ancestors. My cousin flew his Grumman Ag Cat down a dirt road in front of his house.

Single Engine Air Tankers [SEATs] or Fire Bosses come in two configurations. On seaplane floats with wheels [Fire Boss] or wheels only [wheeled SEAT]. Fire Bosses [amphibious SEATs have bigger engines and can scoop water from the nearest river or lake. No time wasted returning to the base for more water or retardant.

Dauntless flies 13 turbine-powered AT-802F “Fire Boss” equipped with aftermarket floats made by a Minnesota company called Wipaire. You won’t remember the name but you will be impressed by the fact that a Fire Boss on floats can scoop up 800 gallons of water in a matter of seconds before returning, again and again, to a nearby wildfire. This scooping ability allows the Fire Boss to deliver an average, 6,000 to 10,000 gallons per hour for 3.5 hours. In comparison, most of the LATs, other than the DC-10, carry 3,000 to 4,000 gallons of retardant and tend to make one drop per hour.

Obviously, the LATs carrying capacity is far greater than that of a Fire Boss, but that isn’t the point. The point is that a Fire Boss can be stationed in the middle of nowhere, reach a wildfire in a matter of minutes and can return to the fire with additional water for 3.5 hours before it needs to refuel.

As Muhammad Ali – then known as Cassius Clay - famously predicted before whipping Sonny Liston in 1964, “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” Swooping low to the ground, LATs are favorites for television reporters, which is why their retardant drops are also known as “CNN drops.” Great theatre but no butterflies or bees here.

LATs under contract to the Forest Service are tethered to major airports with retardant storing and pumping facilities, often hours distant from the fire. There are only 63 large retardant bases west of the Mississippi but there are - but there are thousands of smaller airports that Fire Bosses could use.

None of this jelled in my mind until I stumbled across a third story last month. It was written by Chuck Sheley, the 81-year-old managing editor of S_MOKEJUMPER,_ the exceptionally well-done flagship publication of the National Smokejumper Association.

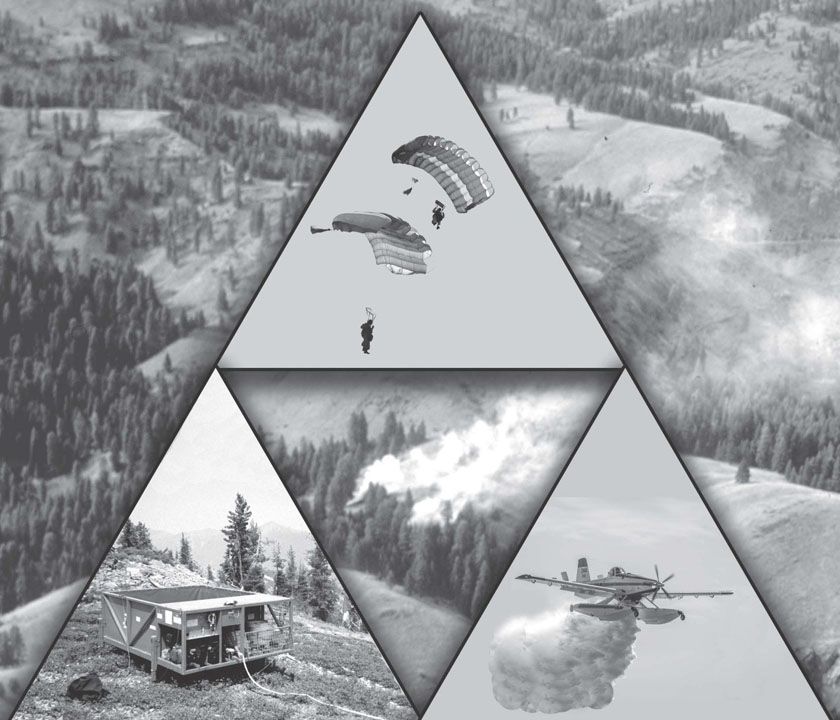

Sheley’s cover story, “Save a Billion Dollars a Year: The New Fire Triangle,” makes a rock-solid case for [1] speeding wildfire response times by redeploying jumpers as they were deployed in the 1940s – when the Forest Service goal was to have a fire under control by 10 a.m. [2] allowing Fire Bosses to provide close air support for smokejumpers on the ground and [3] stationing Klump Pumps near smokejumpers. More of these pumps in a moment.

Why speed wildfire response time? Well, as Sheley explains, the United States is a post-industrial society of nearly 330 million people. We no longer have the option of allowing fires to burn themselves out naturally. Many reasons why, but Sheley believes none is more pressing – or costly – than the billions spent treating wildfire smoke-related illnesses.

I share Sheley’s concerns about the increasing frequency of smoke-related illnesses, which is why there is a chapter in First, Put Out the Fire! titled, “How many cigarettes in a burning tree?” QR codes at the bottom of Pages 119, 120 and 125 lead to a wealth of information about the chemical composition of wildfire smoke, much of it developed by the Forest Service.

Smoke is not the only worry. Most of the West’s municipalities – including Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco - get their water from forests that also provide habitat for fish and wildlife and year-round recreation opportunity for millions of people.

And then there is the soaring cost of fighting increasingly frequent and deadly wildfires – amounts now measured in billions of dollars.

“The annual expenditure for fighting wildfire increased to almost $3 billion in 2018, more than 12 times the amount spent in 1985,” Sheley wrote. “Bottom line, unless you live on Mars, you can see that we have a critical situation – I would call it a national crisis.”

It is a crisis indeed, and Sheley’s claim that the Forest Service could save $1 billion annually is easily tracked, but it was the aerial ballet he described that told me I needed to talk with Brett L’Esperance about his Fire Bosses.

“Just imagine it,” Sheley wrote of his yesteryears. “You have smokejumpers working beneath a Fire Boss and nearby on the ground, 2,200 feet of fire hose connected to a [flyable] 1,000-gallon water tank [the Klump Pump] with a helicopter [to refill the tank]. Constant attack from ground and air. Most wildfires could be quickly extinguished for a fraction of today’s cost. Lives and property saved, and forests protected. Isn’t that how it’s supposed to be?”

Petersen: Brett, I assume you have read Chuck Sheley’s essay concerning the billion dollars a year the Forest Service could save by speeding initial attack.

L’Esperance: I have and being in the aerial wildfire attack business, I agree with his conclusions.

Petersen: You are the CEO and a shareholder of Dauntless Air. Tell us a bit about your company.

L’Esperance: Dauntless used to be called Aero Spray. It is based in Minnesota and was owned by John Schwenk. John’s business was confined to ag spraying until he got into fighting wildfires in 1997. He soon discovered that it came with a lot of added costs, challenges and often - headaches. I was part of a group that bought the company in May 2017.

Petersen: Just in time for a terrible wildfire season.

L’Esperance: It was a baptism under fire.

Petersen: And you gave the company a new name. Why Dauntless?

L’Esperance: We did.

Petersen: Why?

L’Esperance: Two reasons. The aerial firefighting industry has a name problem. Aero Spray, Aero Flite, AirSpray, Aero Tech and others all compete in this space. But no one in the industry has ever tried to differentiate themselves by name or logo. I wanted to do it. I wanted our name, logo, and mission to signify values the public we serve could identify and respect.

Petersen: And the second reason?

L’Esperance: Our chief pilot is a World War II buff. We got to kicking around the name Dauntless because the Douglas Dauntless dive bomber played a significant role in our victory in the Battle of Midway. Wildland firefighters and firefighters in general are undaunted in their work. So are our pilots, crew chiefs and mechanics. The word “Dauntless” seemed like the perfect crossover connecting our Rapid Initial Attack mission with the greatest dive bomber in Navy history.

Petersen: Are you a pilot?

L’Esperance: No, but my dad was in the Air Force and my brother flies for American Airlines. My forte is managing and improving companies. I worked for Bain Capital for several years and, for a time, ran a Bain Capital portfolio company that was the largest operator of Bell helicopters in the United States.

Petersen: Did Bain help you with Dauntless?

L’Esperance: No, we are much too small for Bain Capital. Our financing comes from a New Hampshire firm that manages investments for two insurance companies that prefer smaller, longer term investments like Dauntless.

Petersen: And you fly the Fire Boss because that’s what Mr. Schwenk flew?

L’Esperance: To some extent yes, but we also believe the Fire Boss is the perfect combination of airframe and powerplant for aerial firefighting. We own 12 of them now. We lease another one from the OEM and we are buying two more later this year. Equipped with floats, our planes can leave a base loaded, fly directly to the fire for the first drop, then scoop up another 800 gallons of water from a nearby river or lake in 45 seconds. They return to the scene of a fire in minutes and continue doing the same loop for 3.5 hours without refueling.

Petersen: Very impressive.

L’Esperance: We think so. Put one of these over a team of smokejumpers, hotshots or other ground forces and you have the best Rapid Initial Attack combination possible. A skilled pilot can complete water drops with pinpoint accuracy. Plus, our Fire Bosses are infra-red equipped, so our pilots often see hot spots better than the firefighters on the ground see them. Our goal is to help wildland fire fighters do their jobs faster and safer than any other method allows. That accuracy and efficiency combines to less time needed to get control of a fire.

Petersen: And yet the Forest Service has shied away from the Fire Boss because it is a single engine air tanker or SEAT. Why? There is no evidence that single engine airplanes are less safe than multi-engine planes.

L’Esperance: Correct on both fronts. Historically, they have not contracted with any SEAT operators even though there is A LOT of data that says single engine aircraft are as safe as multi-engine aircraft.

Petersen: So how do SEATs currently fit within the Forest Service’s aerial firefighting framework?

L’Esperance: The Forest Service relies on the Bureau of Land Management and the Bureau of Indian Affairs to contract with us. In years past, the Forest Service has used our Fire Bosses through our Call When Needed [CWN] contract with the BLM, so we believe the Forest Service sees value in the Fire Boss. The challenges have come when the Forest Service has wanted Fire Bosses, but we were already sold out through other contacts. This happened in 2018.

Petersen: Where did it happen?

L’Esperance: It happened in Oregon and northern California. The Forest Service called for six Fire Bosses in August and the Oregon Department of Forestry called for five in late July. In both cases, all our airplanes were already committed to other locations.

Petersen: How might state and federal agencies work around this?

L’Esperance: With Exclusive Use Contracts. EUs allow us to preposition Fire Bosses for a specific time period, typically 75 to 120 days. Flight hours are not guaranteed, but we are paid standby time to be there and ready to fly. Thirteen of the Forest Service’s 28 LAT contracts are EUs. The rest are CWN’s. CWN contracts are almost always more expensive and if you are calling for aircraft through that type of contract, it typically means things are already burning pretty badly.

Petersen: So even the big beasts may or may not be available.

L’Esperance: That is correct. With only 28 of them to spread around during the fire season, often a USFS Region will hold on to an asset to make sure they have coverage in that area, even when another area might need an aircraft. It’s not because they don’t want to help, it’s more because with such a limited number of LATs, once you let it go and fire breaks out in your region, you may not be able to get it back! This scarcity of LATs combined with the Forest Service’s somewhat reticent use of wheeled SEATs and Fire Bosses, of which there is almost 100 in total, leads to a growing number of Unable to Fill Requests (UFRs). On average, over the last five years, almost 25% of the time an incident commander calls for a LAT, the order cannot be filled, leaving that fire without any aerial coverage.

Petersen: How many Fire Bosses are flying today?

L’Esperance: About 110 worldwide. There are 19 here in the U.S., 25 in Canada and the rest operate in Spain, France, Portugal, Turkey and Australia. And they are not cheap. New they cost about $3.2 million apiece and really no used market as of yet because they’re so valuable as a cost-effective firefighting tool, no one wants to give them up!

Petersen: I notice you use the term “Rapid Initial Attack” to distinguish “Initial Attack,” which is the National Wildfire Coordination Group term that the Forest Service uses. Why?

L’Esperance: The suggestion came from a Forest Service fire manager. Once he understood how quickly our Fire Bosses were arriving on the scene, he suggested we use a term that would distinguish the difference between their 3-6 hour Initial Attack response times and our 30 to 45 minute response times.

Petersen: Well, less than an hour certainly beats 3-6 hours.

L’Esperance: It is all about acres, lives, property, and money saved. The larger a fire gets the more money it costs to contain it and the more lives, property, and forest you place at risk.

Petersen: It sounds like you are having better luck working with western states than you are the Forest Service.

L’Esperance: The philosophies are profoundly different. Every state has the mandate to put fires out as soon as they are identified, and some states bear fiduciary responsibility for state-owned trust lands that provide significant revenue streams for schools and other publicly funded institutions. The Forest Service does not have that mandate. They can “manage fire.” This creates a different mindset from the get-go.

Petersen: According to Mr. Sheley’s SMOKEJUMPER essay, it costs taxpayers $25,000 to $30,000 a day to have a fire-retardant equipped LAT standing by, meaning sitting on the tarmac waiting for the phone to ring. Actual flight time is another $10,000 to $18,000 an hour. But standby time for a Fire Boss is $4,500 and flight time is $4,500. Is this correct?

L’Esperance: It can vary a little, based on the type of contract, but you’re close.

Petersen: So if we accept $48,000 a day as the cost to have a LAT on a fire for one hour and $9,000 a day as the cost for a Fire Boss on a fire for an hour it looks to me like the Forest Service could deploy five Fire Bosses for the same money as it can deploy one LAT and cut response times from many hours to minutes. Do I have this about right?

L’Esperance: You have it about right. LATs still play an important role in aerial firefighting but I am a huge believer in the Fire Boss. Our ethos is all about keeping small fires small.

Petersen: Amen to that. You reference a RAND Study - 2012. concerning wildfires. I do not believe I’ve seen it. What did it say?

L’Esperance: It documented the fact that two-thirds of historical forest fires were within an effective distance for using water scooping aircraft like the Fire Boss. Of course, it is not possible to immediately contain all fires starts, which is why a large array of wildfire fighting assets are needed.

Petersen: True enough, but your mindset reminds me of a quote attributed to Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest: “Arrive first with the most.”

L’Esperance: If we apply a military mindset to fighting forest fires that threaten property and lives and consider these “bad” fires as National Security Threats, we would use the existing aerial firefighting assets in a different manner.

Petersen: How so?

L’Esperance: In almost every case, we should lead with the most deployable, cost effective, firefighting effective and highly accurate smaller Rapid Initial Attack aircraft. This includes Fire Bosses, wheeled SEATs and Type 3 helicopters. In total, there are about 200 of these assets available to be the Quick Reaction Force (QRF) that aims to respond very quickly. This keeps a fire start small and cool enough to ensure that the ground troops can contain and control it quickly.

Petersen: A proactive strategy.

L’Esperance: It is easier to spit on a burning match and put it out than it is to put out a house fire with a five gallon bucket - that you need to refill 100 yards away from the house.

Petersen: Good analogy.

L’Esperance: Most of the time, but mother nature still creates situations where even the best Rapid Initial Attack can be overwhelmed. So, when the RIA aircraft are struggling to contain a quick moving fire, send in one or two of the only 28 LATs that exist that are at the Forest Service’s disposal. This makes fire sense, common sense, and dollars and “cents.” Why don’t we?

Petersen: It is a bit like having one big fire truck station in the nearest big city and hoping it can get to your suburban house before it burns to the ground. Or we could have smaller fire stations strategically located in neighborhoods.

L’Esperance: I was sitting in a meeting following the November 2018 Camp Fire. I watched a woman who had lost her home become visibly angry when she learned that the Forest Service only has about 28 large aircraft under contract. She had thought they probably had as many aviation resources as the military. She became even more angry when I explained what the Fire Bosses could do.

Petersen: 85 people were killed by the Camp Fire and more than 18,000 structures, mostly homes were destroyed. I included excerpts from the 911 transcripts in my book, calls from frantic people needing help that never arrived.

L’Esperance: And I fear we have not seen the worst of this crisis. Lots of history and politics involved. You cannot put the blame for this on wildland firefighters. They do a marvelous job, but we believe we can help them do a better job in less time for less money and less risk to their lives.

Petersen: And now we have the coronavirus and social distancing on fire lines and in fire camps. We understand this is causing the Forest Service to rethink the way it deploys personnel and equipment. Might this favor a more rapid initial attack than we have seen in recent years?

L’Esperance: Far be it from me to try to second-guess the Forest Service. I am aware that many in the western congressional delegation are asking some tough questions about the way the agency will handle COVID-19.

Petersen: Might this favor the Rapid Initial Attack approach Chuck Sheley describes in his SMOKEJUMPER essay with Fire Bosses providing aerial support for jumpers and hot shot crews?

L’Esperance: It should but we have not heard anything that suggests any change in the way the Forest Service thinks about SEATs and Fire Bosses. We hope someday they will set up exclusive use contracts with Fire Bosses. Meantime, we hope we can supply them, when needed, through our BLM contract.

Petersen: So, the action for you will probably remain with the states, the BLM and the BIA. In that context, you have moved your maintenance operation to Pappy Boyington Field in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, about 15 minutes from our home.

L’Esperance: We did indeed. It is a great airport and community. It is also strategically located within easy reach of forests in northern Idaho, eastern Washington and northwest Montana.

Petersen: We have reviewed the educational material you’ve developed to explain the benefits of your Rapid Initial Attack philosophy. We will be posting some of it in support of this interview. Is there anything else we can do to help you?

L’Esperance: There isn’t anyone in your business who does what you do as well as you do it. Keep doing what you do I’ll look forward to meeting up with you this summer at our Boyington Field facility and letting you climb around our Fire Bosses.

Petersen: Sounds like fun. If you have the time, we will take you fishing.

You 100% tax-deductible subscription allows us to continue providing science-based forestry information with the goal of ensuring healthy forests forever.